This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

When I picked up my newspaper from the sidewalk Monday morning and saw this picture, I was transfixed.

At a protest for Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge, a calm Ieshia Evans offers her wrists to the police. Something about the movement of her skirt makes her look other-worldly, almost angelic. The police arrested her and also provided the world with the latest iconic picture of a female stand against violence. Ieshia’s powerful calm has gone viral and been discussed in media like the Philadelphia Examiner and the Washington Post.

Images of women participating in civil unrest—or symbolizing war—are surely among the most powerful, imprinting images one knows. Even though I wasn’t yet reading the paper in 1972, I know the photograph of the little girl burning from napalm by memory. Kim Phuc was taken for medical help by the AP photographer, Nick Ut and survived her terrible burns. Kim emigrated to Canada and has given interviews about the events of that day and what happened since the war. Her image became a testimony against war.

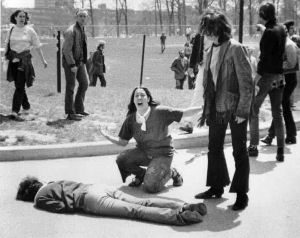

At a Kent State University rally against the Viet Nam war, the Ohio National Guard shot dead four unarmed students in 1970. I can practically hear the screaming and smell tear gas in the black-and-white freeze-frame of anguish. Mary Ann Vecchio, a 14-year-old staying near the campus, had attended the rally and grieved the shooting death of Jeffrey Miller. A photojournalism student, John Filo, shot the picture and won an Pulitzer. He has spoken about feeling guilty that Mary Ann might not have wanted to become the public face of the student struggle against war. But she holds no grudge. In the decades since, these two have participated in several forums on Kent State.

What about the women who would not normally show their faces due to community custom and then discover their images broadcast worldwide? A famous photograph, shown repeatedly in magazines and posters, is known by the shorthand “Afghan Girl.” Sharbat Gula, a young orphan, was photographed in a Pakistan refugee camp in 1984 for National Geographic. Sharbat’s haunting eyes seem to tell the world everything you didn’t want to know about what refugee life is like. Sharbat went on to marry young and live an extremely hard life with her husband and children in the mountains of Afghanistan.

Women protesting during the Arab Spring revolutions throughout the Middle East in 2011 were widely photographed. Seeing colorful, modern headscarves draping passionate political protesters broke stereotypes about the passivity of Islamic women. The aftermath of the Arab Spring has brought continuing unrest and violence, but looking at these pictures at the time of the event, I shared these women’s hopes.

Why do we react so strongly to pictures of women caught up in conflict? I suspect that women offer society palatable images of emotion, laced with vulnerability. Would men’s faces and bodies communicate that as well? Can we bear to see a man cry, or hold out his hands for shackling?

The other side of the coin is that we have many armed women serving in the military and police who are part of these scenes, too. I’ve not yet seen an iconic photograph of unrest where the restrictive element is a woman carrying a gun.

I’m sure it’s coming—and we will be disturbed.