This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

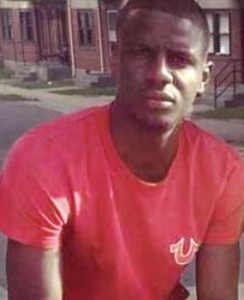

The Vidocq Society is a small but legendary group of experts who gather to solve mysteries of the ages. I wish they could find the answer to an unexplained death that took place a few miles from me, last spring. This is the death of 25-year-old named Freddie Carlos Gray, Jr.

On April 12, 2015, Freddie made eye contact with a police officer in his Baltimore neighborhood. He ran, and a group of cops that included some bicycle officers caught him. He was searched, found to have a small switchblade (legal for the state of Maryland but not for Baltimore City) and was taken into custody. Some spectators observed police sitting on his neck and bending his legs backward. A civilian-shot video shows him being dragged and loaded into the back of a police van. In the van, the police put him in wrist and ankle restraints—but the seatbelt that was also in this section of the van wasn’t used.

The van made five stops before reaching the Western District police station. Freddie asked for medical help several times. When the van reached the police station more than 45 minutes after loading up Freddie, he was unresponsive. Freddie was taken to hospital, where doctors discovered he was in a coma and had severe spinal cord injuries. He died April 19, 2015.

This death, coming on the heels of so many other police-on-civilian killings nationwide, was not going to fade into oblivion. For a few weeks, the city’s reaction was many protest marches, rallies and discussions. But the night following the funeral, a protest became aggressive, with bottles being thrown at police. Thirty-four arrests were made and fifteen police officers suffered injuries.

The next day, the Metro Transit Administration made the fateful decision to stop bus and light rail service in an area where several high schools converged. Some frustrated students grew into a bloc that began vandalizing cars. Earlier that day, some students had spread word through social media that there would be a “purge” with violent behavior.

The students’ riot was quickly augmented by other, older people, who joined in burning buildings and cars, looting stores, and attacking some drivers of cars. Throughout this, the police stood back, and the violence spread like wildfire throughout city neighborhoods. What was happening was about much more than the death of Freddie Gray. It had become an uprising of disenfranchised people frustrated by city government and a lack of opportunity.

The National Guard arrived and the city went under a 10 pm curfew for almost two weeks. The Baltimore State’s Attorney, Marilyn Mosby, announced that her department had launched an independent investigation and would be prosecuting the six police involved on numerous charges. The most serious charge, depraved heart murder, was leveled at the driver. What was unusual about the prosecution was that Mosby announced the charges without waiting for results of the police department’s investigation or sharing the results of the autopsy, wherein an assistant medical examiner declared the death a homicide, due to injuries sustained through omission of safety procedures. The autopsy also revealed the presence of cannabis and opioids in Freddie’s system, which could be argued might have led to Freddie being restless and physically panicking in the back of the van. The autopsy was the only factor presented to convince a grand jury to bring the officers to trial.

The State’s Attorney’s thesis was the officers had conspired to give Gray a “rough ride” to prison, and that was equivalent to homicide. Yet as three officers of the six officers have come to trial over the last eight months—none of them testifying against each other—no evidence of violence has appeared. The result is one officer had a mistrial; and two were acquitted. The three officers remaining to be tried are asking for charges against them to be dropped.

With a supposed absence of violence, how did Freddie Gray die? Was it just a crazy accident in the van the man caused to himself by moving around?

Another possibility might be that his neck was broken by one or two of the officers before being loaded into the van, and the long delay in medical help proved the final death blow. Apparently, the prosecution had a piece of extra evidence they wanted to present in the recent trials. This information was ruled inadmissible, because prosecution apparently hadn’t gone through the standard process of sharing the information with the defense.

The mystery boils down to how a man who was fit enough to run away from the police without any trouble would lie unconscious with a broken spinal column, less than an hour later.