This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

Kitab is the Urdu/Hindi word for book and is pronounced just as it sounds. I find it a lovely word.

So too was my recent book tour in India for A Murder on Malabar Hill, A Perveen Mistry Investigation. You might notice the similarity in title to The Widows of Malabar Hill, my novel which came out this past January from Soho Press in the US. That’s because it is the same book, retitled by my South Asian publisher, Penguin Random India. They wanted to make no bones about the fact it is a mystery.

India doesn’t have a large number of indigenous mysteries, but it has billions of regular readers. In fact, 43% of Indians report reading books every week for pleasure. The world’s fastest growing economy has had a leap in the number of boys and girls in K-12 education. As a result, the largest selling category of books in India is educational. It makes sense: parents are investing in their kids.

A Murder on Malabar Hill was hitting the shelves at the same time a very big bestseller was launching from the same publisher. In a sense, it was like my recent experience of having Widows released at the same time as the White House tell-all Fire and Fury. I was sitting in a car with a sales rep whose phone would not stop ringing with orders from booksellers wanting one hundred to one thousand copies of Exam Warriors.

The startling thing about this children’s educational book is that its author is India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi. Exam Warriors hits publishing’s sweet spot because is a how-to study workbook for children, featuring 25 mantras for studying and reduction in stress. It includes yoga exercises and is illustrated in cartoons. Priced at a bargain 100 rupees (about US $1.60), it is affordable to many and published in English and Hindi.

Back to A Murder on Malabar Hill. So far, it’s just in English, and it costs a lot more than the Modi book—399 rupees. My novel is being published in English, and one of the amusing aspects to the copy edit was turning American English into British English. Some revised spellings of words for India were practise for practice, and jewellery for jewelry.

With English language being a subset of India’s vast book market of 22 official languages, I was interested to see that brick and mortar bookstores were nevertheless dominated by English language books. The majority are Indian authors writing in English, but Dan Brown is big, too.

I enjoyed a number of bookstore visits in Delhi, Mumbai and Ahmedabad. One store in Mumbai was actually called “Kitab Khanna.” With my limited Hindi, I thought the store name meant something like “books food.” However, the way Khanna is spelled in the store name makes the meaning a “Book Box.”

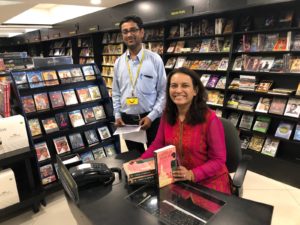

Visits to places like the independent bookstore Kitab Khanna, as well as multiple locations of the small chain stores Crossword, Om Books, Full Circle Books and Bharison’s, were a very special opportunity. Sales reps for these stores brought me in to sign newly-arrived books and talk about the book’s heroine to the salesclerks, who’d be better able to explain it to customers. This has never happened to me in the United States. I also did radio interviews on 3 different pop FM radio shows, two of which were syndicated.

I did have a couple of book talks and signings, but they were not in bookstores. No—in India, a book signing is closer to theater!

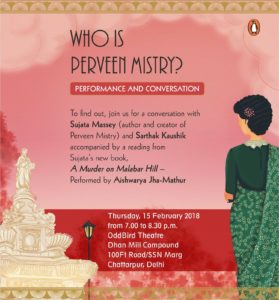

My biggest event was in Delhi at the intimate OddBird Theatre within an old mill complex in the Chattarpur district. My editor had arranged for a talented local stage actress to read a chapter of my book aloud. The actor, Aishwarya Mathur-Jha, had dressed in an antique lace sari and arranged her hair in a curled updo typical of the time period for Parsi women. She became my character, Perveen Mistry. Her reading was powerful and had the large audience spellbound. For me, it was magical to hear my written words uttered by someone with the right accent and intonations. It’s a concerted effort for me to write dialog in Indian English; so when I heard the Aishwarya’s dialog sounding as natural and passionate as she made it, I was heartened. All I had to do after being transfixed by Perveen Mistry on stage was chat about the book with RJ (radio jockey) Sarthak Kaushik, as radio hosts are called. Lots of jokes and good fun.

The second book event was in Mumbai. This was an interview with a journalist, Jane Borges, who was working on an article about the book that came out a few days later in a newspaper called Midday. Jane’s interview and my reading was held at a small cafe where every table was set with delicious cookies. It was a small event, but the questions were good, and so were the treats.

Another event that was a new thing for me was a meet-up with book bloggers. About ten bloggers—all quite friendly with each other—showed up to the new Bharison’s bookstore in Delhi’s posh Gurgaon suburb. They’d read advance copies and peppered me with good questions. Many selfies and even a short film made by one blogger appeared very quickly after the event.

Speaking of social media, the publisher shared the surprising news that movie star Amitabh Bachchan had tweeted a photograph of his adult daughter reading in his home. If you zoom in on the book in her hands, it turns out to be A Murder on Malabar Hill. Somehow, this woman had a copy of it before it reached the bookstores. Nobody could figure out how.

Perhaps it’s just pure marketing magic. I met with some future marketing geniuses—India’s business students—at the Indian Institute of Management Udaipur’s Leap Year Literary Festival. The kids had taken their Sunday to sit and listen to six of us—authors, comedians and screenwriters—talk about our work. It was a pleasant surprise that business students would care enough about creative writing to organize a writing festival.

But this is India. After all, the prime minister has written a dozen books!