This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

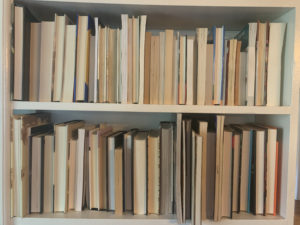

I was messing with my books today and turned them so that the spines were hidden. No titles, no idea of content. They seem like a visual representation of how powerless books are if we don’t see what they’re about.

Blank books remind me of silenced voices. The volumes make me think of the growing movement inside the United States to ban books from schools and public libraries. In 2021, almost 2000 titles were challenged by citizens, according to this recent New York Times article. Much of the banning action is in states like Florida, Georgia, Iowa, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee and Texas.

The book challenges bring back memories of my own relationship with libraries. Back in my 1970s and ’80s childhood, we were regulars at the public library. My mother usually drove me and my two sisters to the Ramsey County public library once a week, sometimes twice during summer vacation. I walked to the beautiful little Carnegie Library in neighboring St. Anthony Park myself, and of course, I always got books from the school library when my class had visiting time. My father always gave us books specially chosen for our particular interests at Christmas and birthdays. He still does; and I do the same for him.

I recall vanishing into the faraway, much more charming worlds of these library books. I adored a series about a Jewish family in turn-of-the century Brooklyn (All of a Kind Family). I marveled at the hardships of pioneer children in the Midwest (the Little House books), and the fantasy landscapes in The Dark is Rising Sequence. My sisters and I also read close to one hundred Amar Chitra Katha children’s comic books that my father got for us in India. This Indian publishing house, founded in 1967, specialized in the pictorial depiction of religious stories, epics, folktales and South Asian history. The comics felt special because they told me something about the country of my heritage, when the libraries had no books about it except for those by British Colonials. As my sisters and I matured, we were attracted to reading darker themes, especially books set during World War II that detailed the Holocaust. With the other half of my personal identity rooted in Germany, I felt a dissonance between my own experiences in the country and the history emerging for me in literature.

I recall a handful of children’s books with Black characters. However, when I recently researched the books’ authors, I discovered they were all White. In my late teens, the first African-American author I read was Maya Angelou, followed by Alice Walker and Toni Morrison. As a teenager, I finally got a peek behind the curtain shielding the mysterious and alluring world of sex. My favorites were Rosemary Rodgers’ Sweet Savage Love, and an erotic essay collection by Nancy Friday, and the ultimate mind-blower, Rita Mae Brown’s tour-de-force novel about lesbianism, Rubyfruit Jungle. Not that these particular titles were carried in any of my libraries: I remember buying My Secret Garden using my weekly allowance, and getting a battered second-hand copy of Rubyfruit Jungle handed to me by one of my sisters.

Prior to 1999, most books removed from school libraries were done so due to profanity and sexual or political content. Think George Orwell’s 1984 and J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye and Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

The next area where books were attacked was in a perceived threat against Christianity. I remember back in the early 2000s, some conservative parents had success banning J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books using the argument it encouraged witchcraft.

One of the strangest recent bans is against mathematics textbooks in Florida. Its Governor, Ron DeSantis, has not named the titles of the books involved, nor the instances, but the state department of education has rejected 70 percent of math materials for K-5 students, 20 percent of math material for Grade 6-8, and 35 percent of the math materials for grades 9-12. With the hiding of book titles and any excerpts deemed offensive, it seems absolutely crazy that this recall could succeed. He’s also requiring all schools to provide a searchable list of all books in their libraries for parents, and to continue updating parents with details of every book that the school acquires.

After looking at the lists of the most banned books in the United States, I’ve come away with the impression that the challenged books are mostly be by LGBTQ authors and writers of color.

Here is a tiny sampling of some of the most often-contested books that some people are trying to keep out of libraries.

Nonfiction

Caste by Isabel Wilkerson

Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates

The End of Policing by Alex Vitale

Fiction

The Autobiography of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie

Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neal Hurston

To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

Beloved by Toni Morrison

The Color Purple by Alice Walker

The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas

Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You, by Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi

All American Boys by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely

Are you wondering exactly who the people are who are fearful of books about social issues?

Often, they’re parents who complain to a teacher or principal. Or library volunteers quietly snapping pictures of books that they are shelving. They could be church or political party members taking their issue with a book to a lawmaker who wants their support.

In Virginia, just south of my home state of Maryland, Glenn Youngkin ran for governor promising to prohibit teaching of course material that addresses the history of racism (in his words, critical race theory). He won the election.

Texas State Representative Matt Krause is running for re-election in a tightly contested primary. He created a list of 850 children’s and young adult titles he believes could make youth feel uneasy or uncomfortable or guilty. He sent it to the state’s school boards and asked them to let him know whether they had any of these books in the school libraries.

Censorship activism has been nicknamed by some as the Ed Scare as a reference to the 1950’s “Red Scare.” Seventy years ago, people were so afraid of losing their jobs that they signed oaths professing no connection to the Communist Party. Today, librarians might keep a book behind a counter, or teachers would think carefully about what they can share during read-aloud time. Some of the proposed bills could criminalize the teaching of a book that someone judges to be obscene.

Last week, I received an email from one of my past publishers. Jonathan Karp, the CEO of Simon and Schuster, wrote to its authors about the publisher’s intention to stand firm and keep publishing books without fear of censorship. It also included resources for readers and writers to fight book challenges.

The New York Public Library and the Brooklyn Public Library are allowing people across the country who aren’t NYPL cardholders to borrow banned books as digital downloads. It’s a generous move made to support access, but it also reveals the tragedy of how different library culture is from state-to-state. After all, the people in Texas and Florida pay taxes to support these libraries, so they can have access to what they want to read.