This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

These days, photography seems to have become an expected skill for writers. Confession: I like to take pictures, but I don’t understand how to artfully compose them or wait until the right moment to get a great shot. I wish I’d learned more during my years as a newspaper features reporter, because so many photographers were working just over my shoulder.

When I think back on that era—the late 1980s—I remember that out of the newspaper’s whole photography department, just two photographers were women. This was a significantly greater gender gap than among the newspapers reporters, although there were many more males than females in the newsroom.

The composition of my newspaper’s staff made me all the more surprised and impressed to learn about India’s first woman photojournalist, Homai Vyarawalla. I first heard this name in a conversation with a smart and famous Bollywood actress. She said to me, “You probably already know about India’s first woman photojournalist, who was working in British India during the time of your books…”

I didn’t know anything about her. But I was intrigued.

Homai was born in 1913 into a priestly Parsi family who moved from Gujarat to Bombay for a better life; her father worked in the fledgling film industry that later became known as Bollywood. Some accounts say that Homai married at age 13; other accounts say that at 13, she met the man whom she later married. The gentleman in question, Manekshaw Vyarawalla, was both an accountant and a photographer. After high school, Homai went to Bombay’s famous training school for artist and artisans, the Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy School for the Arts. Homai was interested in painting, but because the new field of photography was booming and had paying jobs, she went for the latter. Her first jobs were snapping pictures of women and often went into the Bombay Chronicle. She earned one rupee per published picture.

Because Homai was a woman, she wasn’t considered a trained and reputable photographer, and she therefore had to use her husband’s name on her work. Later on, when she was accepted as a working photographer, she created a catchy professional name: Dada 13. This was a combination of her car license number, her birth year, and the age she was when she met Manekshaw.

During Homai’s years in Bombay, her pictures had a wide range of subjects, but during World War II, she and her husband shifted to New Delhi, and she was hired by India’s ministry of information to take official photographs as part of an imperial propaganda force: the British Information Service. (In my novel The Sleeping Dictionary, this was the kind of work Mr. Lewes undertook during the war). While Homai was shooting pictures for the government, Manekshaw Vyarwalla managed the studio and dark rooms where the film was processed.

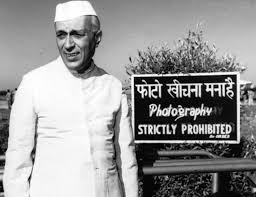

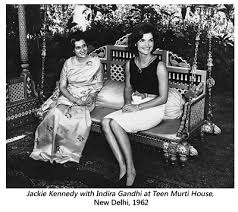

Homai now had front row access to shoot both staged and candid photos of famous politicians and visitors to India. Among her typical subjects were Mahatma Gandhi, Lord Mountbatton, the Dalai Lama, Indira Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, whom she considered her favorite subject of all time because he was both photogenic and fun to be with. Homai’s photographs were always shot in monochrome and processed by her; they are mostly part of the Alkazi Collection of Photography in New Delhi. Some of her most famous photographs are gathered in this story by Catch News. After the British were gone and there was no longer a need for British propaganda, she worked for the Illustrated Weekly of India, which ran from 1880-1983 and was kind of like Time, Newsweek and People rolled together.

Within the press corps, Homai Vyarawalla was a standout, with her practical but elegant short hairstyle and trademark sari or salwar kameez. Although many Parsi women felt free to wear dresses instead of saris, she chose the sari as her daily dress probably as a means of securing a bit of respectful distance at the chaotic, male dominated events. Yet she was no shrinking violet. Homai carried her own cameras, rode long journeys to get the pictures she needed, and did not ask for special favors. She talks about her special vintage cameras and the adventures they brought to her in this documentary film by producer CS Lakshmi.

In 1970, one year after her husband’s death, Homai abruptly quit working as a photographer. She was at the peak of her career, but she said she was sick of the rude behavior of the photography corps. She retired to live with her only child, now an adult, and after his death, stayed alone in a walk-up apartment without a telephone in a small town. Far removed from the life she’d once lived close to the top of Indian politics and power, she passed her days quietly and thriftily, sewing her own clothes and doing other homemaking. Yet journalists persisted in visiting to ask about her trailblazing career, before she passed away in 2012 at age 98. Fortunately, she was awarded the Padma Vibhushan, India’s second highest civilian honor, in 2011, when she was still alive to receive it.

Being first at something, and even being very good at it, does not guarantee a long or well-paid or publicly honored career. Such was the situation for Cornelia Sorabji and Mithan Tata Lam, India’s first two women lawyers. But the joy for the ones who come afterward is exploring the records they left for us. These great ladies may not have felt like legends during their lifetime, but the work they left ensured it.