This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

What does it take to bring an idea into book form—and then to take one book into a series?

My first mystery came out in 1997, and it turned into a series that lasted for eleven books. Then I went on to throw myself into a second series that I’m still writing. Doing a series is not only a writing choice; it’s also a commitment to community, both real and fictional.

On the outset, the idea of a series is simple: a sequence of novels with the same protagonist. Yet there are some great permutations. The books could be spearheaded by a succession of linked protagonists, such as the women lawyers in Lisa Scottoline’s Philadelphia series, or the various detectives we meet in Tana French’s police procedurals set in Dublin. In romance series like Bridgerton, a family of brothers and sisters take turns getting romantic fulfillment.

Series are popular because of readers’ deep desires to stay connected with characters they care about. Some critics say the business of writing a series is to essentially replicate the same reading experience for the readers each time—albeit with a novel plot and new supporting characters.

For me, the ‘why’ of a book series is greater than a career formula. It’s truly comforting to me to write novels that revisit the same houses and restaurants with characters that became my friends. I have so many thoughts about what makes series writing wonderful. Therefore, I’m going to make this a two-part blog post. Imagine we are having a cup of tea together and talking writing. You see—you are already a character in my series.

How it All Started

Picture me at age 27, entering the 1990s as a young bride who had left what seemed like the greatest job ever at a daily newspaper. I didn’t want to stop writing—but I had a massive geographic move from Baltimore to Yokohama-area Japan, and my writing job opportunities were limited. So why not try writing fiction? The only other writing job I’d heard about was correspondence secretary for the Officers Wives Club!

I sat in my chilly house with gloved hands in front of a brand new PC, feeling liberated and optimistic. I had no illusions of writing a publishable book. The goal was experiencing what it felt like to write long fiction. I told myself writing time in Japan would be a step in a long climb. Yet that first book I dreamed up became the ‘first in series’ of the Rei Shimura books. I really didn’t know what I was doing; but somehow, it worked.

That first protagonist I created, Rei Shimura, was a Japanese-American English teacher living in modern Tokyo. The position of being a foreign language teacher in Japan is a culturally iconic one that has lots of room for adventure. I myself worked part-time as an English teacher in Japan, not earning much money but gaining so much in terms of cultural connection, whether I was working with high schoolers, military service members or elderly people. Important memo: the more you know about the job your protagonist does, the more interesting and realistic your character will be.

Yet for a teacher-character to continue being innocently drawn into suspicious deaths, year after year, doesn’t feel true to life. I hadn’t thought about this fact when I started, because I expected I was writing a standalone novel. Now I had to twirl creativity and logic at the start of each new book to find a plausible reason for Rei’s abilities and involvement to surpass the Japanese police.

As the series progressed, I became quite annoyed with the recurring problem. Ultimately, I had a spy agency recruit Rei, so she is forthrightly directed into covert investigation—and she has a prickly relationship with her agency supervisor, too. And what a hot relationship that would violate every HR guideline, but of course, this was a magical, fictional world!

In the Rei Shimura series lifespan, the books went through three publishers: HarperCollins, followed by Severn House, and then myself. Perhaps it was because I wanted flexibility in the future that I never have outrightly declared the series is over. I feel terrible disappointing people who have invested years and money in the series. Not only are they buying books for themselves, they are gifting them to others and advocating for the books’ presence in the library system. Dear readers have not only written to me personally, they have nominated me for speaking gigs and awards—unexpected privileges and joys.

I actually was trying to wind things up, yet I still loved the series. Breakups are hard for writers and their characters. Ten books sounded like a complete number of Rei books, but I felt compelled toward writing just one more book.

The last series book, The Kizuna Coast, had Rei investigate a disappearance in the aftermath of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. Once the mystery resolved, we see Rei boarding a train from Tohoku toward Tokyo. Feelings are upbeat, and I hint that she might be entering a new stage in life. And I think that’s the positive feeling that helps a series end, whether or not it’s planned out.

After The Kizuna Coast, I took a deep breath. I wanted a break from the treadmill of a book a year. Self-publishing worked, but it was a lot of extra jobs for someone who wasn’t a trained web designer, marketer or publicist. A traditional publisher was interested, but I didn’t want a multi-book contract. I became a free agent and decided to pause.

My Palate-Cleanser Book

I had a nagging sense that it was time to write about India, the place that was so central to my family history. I’d been spending more time in India as an adult than in childhood. In quite interesting ways, I was getting to spend time and learn from the families of my father, my stepmother, and my stepfather. An idea drifted my way, probably because I wasn’t pushing hard to think something up. And what also was clear is I wanted to take a break from mystery. I wanted to try something I loved reading, but wasn’t sure I could pull off: a historical novel.

This straightforward wish evolved into four restless years of writing and rewriting a standalone novel about a young Bengali woman coming of age in 1930’s and ’40s India. The Sleeping Dictionary was a book that transported me—not just because of the setting, but because of the wealth of details that true history provided. Unsurprisingly, the characters grew on me in the four years that I took to write and revise the book. As it was being readied for publication, I daydreamed about making it a series. Yet as I pondered the type of follow-up this book should have, the answer was a very sober story. I knew what difficult political events marked 1950’s, ’60s and ’70s Bengal. I feared becoming emotionally depressed if I wrote about matters like the kidnapping of women post-partition and the war for Bangladesh’s independence.

This is why I ultimately decided that The Sleeping Dictionary would stay a standalone. At the same time, I realized how much I wanted to write series fiction again. The emotional ride in such books is more predictable and satisfying for me. In my approach to series mystery, the unrest and crime is on a smaller scale—and it’s fictional. Order is always solved by page 400, and the protagonist has time to recoup before the next book.

The Next Series

Second time around with series writing, I vowed to remember as many of the things I struggled with for the Rei Shimura books. My goal was to follow a route that had fewer pitfalls—and to write about a setting that had lots of story ideas.

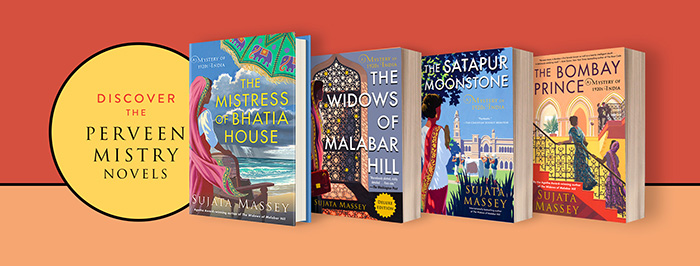

Firstly, I was intent on giving my new sleuth a natural reason to repeatedly encounter crime and suspicious death. No women were allowed into the police until the 1970s in India, so she couldn’t be a cop. However, my years of research in 19th and 20th century India meant I had a big file cabinet, and a specific file that included the names and biographies of two early women lawyers working in British Raj India. I knew I could give my fictional heroine such a real job without bending reality. Still, writing about a female lawyer would be challenging since I was not a law school graduate—and you know how I feel about writing ‘what you know.’ I began looking for people who had studied law willing to answer my questions about the likelihood of a judge doing this, or that.

I also pored over law books published during the British Raj to make sure I had facts rights about laws about crime and punishment, inheritance, and marriage and divorce. I made my heroine a Zoroastrian because the early women lawyers of India were more likely to come from this faith community than others.

I read up a storm to get an interesting and realistic legal dilemma for The Widows of Malabar Hill. And then I returned to the facts surrounding Perveen Mistry, my lady lawyer. A young woman in her twenties is of marriageable age—especially in a country like India. But would a woman be able to practice law actively while married? Given the social constraints of the time, and the likelihood that a female sleuth’s husband could restrict her activities, I decided to make her the equivalent of a spinster; yet with a unique status that would keep her from being able to marry anyone intriguing she met within the series. And this itself became an interesting plot point.

There’s another, often subconscious, decision about protagonist power that writers make. I argue that you can roughly divide the sleuthing protagonists in two categories: superheroes, and ordinary, flawed people. The characters Sherlock Holmes and Jack Reacher are examples of the superheroes, though fans would probably argue they have flaws that make them interestingly human.

Rei, my first protagonist, was an accidental sleuth from the start and she escaped dangerous moments using different forms of soft power. Perveen is closer to a superhero; while she’s not physically powerful, she has extreme courage and social skill that comes from always having to fight for her ability to work and go about in public.

There are so many women I consider superheroes in my daily life in America and also in India. Among the Indian stars are women who have been the first: the first to finish high school in the village, the first to perform surgery at the hospital, the first to drive a taxi. More heroes: the middle-class housewives who make sure the poor kids living in shanties nearby get homework help and schoolbooks; and who don’t hesitate to find a doctor and pay the medical bills for a servant’s wife who needs surgery. These women change and often save lives.

Remembering all this beautiful strength helped me pull my ideas together. After a few months of deliberation and exploratory writing, the characteristics of my series heroine had fallen into place. Miss Perveen Mistry, Solicitor at Law, had both a personal status and practical job for a permanent series position. Yet even more decisions need to be made to build Perveen a successful series to return to, book after book. More about these ideas in the next post.