This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

Nev March lives in New Jersey, and I’m in Baltimore. Our only real life meeting was in New York City at the Edgars symposium in 2019. I was there to win the Mary Higgins Clark prize the following evening (though that day, I had no idea!). Nev already knew she was winning the St. Martin’s/Minotaur Mystery Writers of America Best First Crime Fiction award, which results in publication of one’s book the next year.

Nev intrigued me by sharing that Murder in Old Bombay was partly inspired by one of Bombay’s most famous unsolved crimes: the Rajabai Clock Tower Deaths of 1891. I was honored to write the cover blurb for this book. I found that Nev solves the riddle of the deaths by using fictional characters who come together in a way that makes great dramatic and cultural sense. She also introduces us to a fictional Parsi family of great wealth and intelligence, and a clever young Army captain, Jim Agnihotri, who’s hired to investigate their family’s tragedy.

It was no great shock that this book is also nominated for the Edgar Award nominee for Best First Mystery, but it certainly is great news. I don’t know how things could get any rosier for Nev. But from the answers she gave me, it’s clear that she is one of the humblest, hardest working writers around.

You just got nominated for the Barry and Hammett awards! And you’ve got an Edgar nomination for best first mystery. What does the recognition mean for you and your writing journey?

It’s marvelous. When I was writing I didn’t ever imagine Murder in Old Bombay would find such a warm reception. To have a first book out is both surreal and exciting; to have it gain such recognition is enormously rewarding. It also adds a bit of stress, because now my next book needs to match or exceed this level of writing. My writing journey has just begun, so I have to trust that the process works, and that pulling honestly from my truths will be enough. In some ways it’s a bit easier, because I trust my own judgement more.

We’ve talked together about how important books were in your upbringing. In your childhood or teen years, did you want to become a novelist? What happened instead, with your longtime career in the US?

In 1990 my short story “Must There Be Crying?” was published in Target, a children’s magazine in India, followed by “Blue Skies,” a short sci-fi piece. I was in college; writing was considered a hobby, not a career. After earning degrees in economics and psychology, I won a scholarship to a graduate program in the States. For the next twenty years I worked in business analysis, market research and more, then was laid off.

This led to some soul-searching. I’d enjoyed my work, conversations with colleagues and made good contributions—should I seek another position of responsibility or turn to what gave me more joy—writing fiction? Writing won, but it was a few years until it paid off.

I was born Sujata Banerjee, but took the last name “Massey” when I married my American husband. As you know, Massey also is an Indian name, so it’s proved a miracle surname for me as a writer. Was Nev your nickname or strictly a pen name? Tell us how you became “Nev March.” Do you go by Nawaz Merchant in your daily life?

I’ve experienced many forms of racism over these 30 years, and I wanted to give my book a fair chance. A name is a vanity in some sense, a mark of pride that says, “this is mine.” Murder in Old Bombay is like my adult child that has gone into the world. To prevent my name becoming a barrier to its growth, I chose to write under a pseudonym. My nickname was Nav, which I modified to Nev. “Nev” is a nod to Neville Shute, an Australian writer I admired enormously. I took “March” from a childhood favorite, Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women. Jo March wanted to earn a living as a writer, like me!

How did you tap into your talent and get the courage to believe you could write a novel? Was your writer’s group part of it?

Although I’d written four books before 2006, I didn’t know how to market them. So, with two young kids and a full-time job, I put aside creative writing for a decade. Five years ago I joined my local writers’ group, but it was a year and a half later that I wrote Murder in Old Bombay. My writing group was enormously supportive, but also honest, with tough critiques when needed.

What does writing a 135,000 word manuscript in four months’ time look like? Tell us when you awoke, when you slept, and what else happened.

Writing Murder in Old Bombay was addictive. I’d keep seeing a scene repeating in my mind like a video on endless loop. Each time the scene was from a different perspective, or have additional dialog and surprises. I’d write just to get it out of my head! Then the next would spool. I’d go to bed at 2 am and have to return to the PC at 4 because the next scene kept repeating. It was intense and I loved every bit! It hijacked me—I rarely knew what date it was. Terrified that it wasn’t as good as I wanted, I leaned heavily on my friends during those months. Three critique partners provided extensive input, and one of them, Jay Langley, helped me trim the 138,000 word manuscript to the final 115,000 words needed by my publisher. I can’t ever thank them enough!

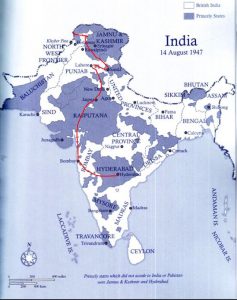

You delve into a true mystery in Bombay, the deaths in 1891 of two young Parsi women who fell from the Rajabai Clock tower on the University of Bombay campus. There were 2 trials with suspects brought forward, but no one was ever convicted. I was deeply struck by the emotion around this case and even refer to it in my next novel, which is set thirty years later. How did you first hear of this crime, and what did it meant to you as a young woman in India? And how did you extract information from more than a century ago?

As a teen, if I tried to do something adventurous (join the hiking club, overnight college trip etc), my parents put the kibosh on it with this phrase: “Remember the Godrej Girls.” It pointed out that girls aren’t safe, even in daylight. Rape was never mentioned, either in public or private. I only knew that something bad happened to girls from my own tiny community.

Decades later I read an article about their deaths and the murder trial, which was the trial of the century in the 1800s Bombay. When the accused with acquitted due to lack of evidence, two petitions were filed by Parsi citizens of Bombay begging to reopen the case. 60,000 Parsis signed the first, 40,000 the second petition. This is astonishing, since there were only 100,000 Parsis world-wide!

To research it, I read articles and newspaper archives—the case was in British newspapers, and biographies of Ardeshir Godrej (the young widower of one of the victims) hoping for more clues. Ardeshir (usually shortened to Adi) fascinated me, because he became a serial entrepreneur, and founded what is now the Godrej Conglomerate. How does a 22-year-old recover from the death of his young bride? I wondered whether he might have solved the mystery by hiring a detective, and thereby found closure. An intensely private man, he wouldn’t have made public his investigation. That’s where my novel began.

The novel’s protagonist is Jim Agnihotri, a dashing young Anglo-Indian military officer. Was he always meant to be the novel’s protagonist? I step out of my exact cultural identity (Indian-German) when writing about India because it feels too unusually specific. What advantage does stepping out of your own Parsi identity to become Jim give you in storytelling?

The moment I “saw” Captain Jim, I knew he’d be the novel’s protagonist. The first scene I wrote was chapter 2: his meeting with Adi. An army man, an officer—I could not understand why he was so deferential to the grieving widower. Then I realized he was mixed race, and it all fell into place. In my mind Captain Jim was astonishingly forthcoming, so I could show his intense loneliness from exclusion.

Parsi writers like Rohinton Mistry, Boman Desai and Bapsi Sidhwa have beautifully portrayed the Parsi community as insiders. I wanted to show my community how they are viewed by others, especially by those who love them, who are traditionally not admitted into the Zoroastrian faith. This loving portrayal allows me to tell tough truths; that those who follow the Zoroastrian path of “good thoughts, words and deeds” may still be bound by old conventions that hurt others deeply. The character of Burjor is based on people I love dearly who I hoped to persuade to a more liberal point of view.

When was the last time you were in India, and when do you hope to return?

I visited India every other year, sometimes three times a year for my parents’ medical care. Mum passed away last year, and Dad is now in the US. Once the covid restrictions are lifted and it is safe to travel, I hope to return and meet my dear aunts and uncles.

Tell us about your next book. Will it feature Jim? Is there a title yet?

No title yet, but I’m working on a sequel set in 1893 Chicago, where millions visit the World’s Fair, the magical Columbian Exposition celebrating America’s progress. Now employed at a Boston detective agency, Captain Jim investigates the murder of a friend on the fairgrounds. The first Parliament of World Religions will be held that summer, while at the same time the World Convention of Anarchists has assembled. What could possibly go wrong? And, yes, what will resourceful Diana do about it?