This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

It started with country-blaming.

China flu, Wuhan Flu, Kung Flu. Donald Trump could only think of blaming outsiders, to deflect attention from his own disinterest in controlling a pandemic. Yes, coronavirus was first identified in China. Yet we’ve learned the virus was already in the U.S. and Europe at that time.

The linking of Asians with contagious illnesses and societal problems isn’t new. Many of us can recall the decline of American manufacturing in the 1970s and ‘80s and the rhetoric against evil Japanese auto manufacturers. Our grandparents remember that during World War II, Japanese Americans were forcibly detained in camps, with their properties stolen by white neighbors, during the time they were away. In 1900 San Francisco, Chinese residents were blamed for the bubonic plague and forcibly quarantined in Chinatown. In 1886, hundreds of Chinese-Americans were forcibly expelled from Seattle. In 1871, the country’s largest mass lynching took place in the then-small town of Los Angeles, when 500 rioters angry over the accidental shooting of a white man chased down all the Chinese Americans they could find. Eighteen were killed, and the few men convicted in the deaths were released on a legal technicality and never retried.

Historian Erika Lee and activist-writer Helen Zia spoke on a Washington Post video interview about why Asian blaming is so endemic in this country. The running theme is that sometimes, when there’s a government or business failure, it becomes expedient to blame it on people perceived as outsiders or invaders.

The nonprofit Stop AAPI Hate is recording what they believe is a fraction of the racist incidents against Asians since last March 19, 2020. By February 28, 2021, the total of community-reported incidents was 3,795. Just last week, 21-year-old Robert Aaron Long was arrested on suspicion of murdering eight people, including six Asian women, at massage parlors. What astounds me is that an officer in the Atlanta police who interviewed the suspect said he had an obsession with women, nothing racist. It came to light later that the officer himself had posted on Facebook a photo of a racist T shirt blaming coronavirus on the China.

After lessons learned from the Black Lives Matter movement this last year, it’s painful that the police, and many of the public as well don’t seem to equate violence against women as having the potential to stem from racism. I believe the fetishism of Asian women by Western men has troubling roots in war experiences and colonialism. Belittling females presents little risk of revenge—and a lot of reward.

I grew up in a suburban Minnesota school system where racist bullying was endemic, from my grade school to the junior high and high school. Boys sing-songed “import” at me during the years of the anti-Japanese car backlash. Girls spoke loudly amongst themselves about how ugly my hair was, or that I was too “dark complected” to get a boyfriend.

All that hurt. But I was only flat-out terrified when I left the Midwest for a trip back to the state where I felt loved—California, where my family had briefly lived during a sabbatical year away from Minnesota. I’d rejoined my friends from eighth grade at Martin Luther King Junior High in Berkeley. We were exploring San Francisco. We were laughing and enjoying ourselves. Suddenly, a white man with wild eyes was screeching and snarling and rushed up within inches of my face.

“You dirty alien. Get out of this country. You’re disgusting! You’re ruining us!”

The words I’m sharing aren’t exact, because there was certainly a lot of profanity I blocked out. I also never knew if he’d singled me out because he thought I was Mexican or Asian. But I was a brown 14-year-old girl, five foot one and just a hundred pounds. He was very, very close to me, and while there were plenty of adults around, everyone appeared to be studiously ignoring the man’s existence.

I’d felt joy in California because I felt it was diverse—but there were Californians who didn’t want diversity. Anti-Asian racists go after those they think can’t fight them—and often, this is assumed to be the elderly, children, and females.

Novelist Angie Kim’s opinion piece in the Washington Post lays it out quite well. I think about the Muslim girls and women attacked after Trump assumed office, and the South Asian women and men of all faiths attacked in response to the 9-11-2001 terrorist attacks.

Last week, Xiao Zhen Xie, a 74-year-old Chinese immigrant from China, was accosted in the same part of San Francisco where I’d been harassed. Like me, she was accompanied by someone standing at a stop light, unable to move because of the traffic. That’s when 39-year-old Steven Jenkins allegedly rushed up and punched her in both eyes. And that’s when she was far more active than I’d been. She managed to grab a board which she used to defend herself against the man—hitting him so hard he fell down and was able to be detained for arrest.

Xiao Zhen Xie fought back. And by flattening her assailant, she probably prevented him from attacking another Asian. He’s suspected of an attack on an 83-year-old Vietnamese man the same day.

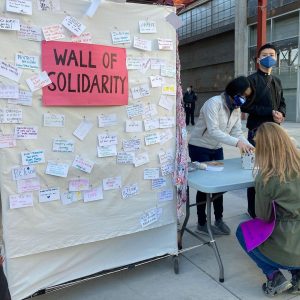

Stop AAPI Hate has 5 concrete steps for people who may spot violence in the street in the next few days, weeks or months. It’s far less in-your-face that what I expected. But in the online vigil I attended last week, mourning the victims in Atlanta, I heard the opinion that vigilantism and policing won’t change things. Respect and peace are the way to win.

- Take action. Go to the targeted person and offer support.

- Actively listen. Before you do anything, ask – and then respect the targeted person’s response. If need be, keep an eye on the situation.

- Ignore attacker. Try using your voice, body language or distractions to de-escalate the situation (though use your judgment).

- Accompany. Ask the targeted person to leave with you if whatever is going on escalates.

- Offer emotional support. Find out how the targeted person is feeling and help them determine what to do next.