This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

A week ago, I walked down to the consignment shop near my house and picked up a fashion mystery.

The mystery came in the form of a long dress of purple-blue printed silk crepe lined in cotton. The stitching was minute and clearly done by hand. Examining the dress, I flashed back to my first long dress and blouse custom-stitched for me at a tailor’s in Hyderabad when I was ten years old.

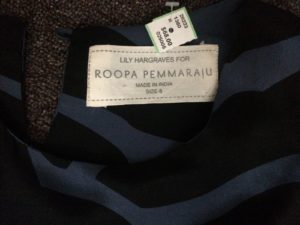

But the pattern was unusual. The silk was printed with thick black brushstrokes that burst like a tree over my legs. The design was not pretty; it was strong and vibrated in a way that reminded me of something strangely familiar, but that I couldn’t identify. The label read Lily Hargraves for Roopa Pemmaraju.

I’d never heard the names, but the funky silk dress fit perfectly and was an unbelievable $68. I snapped it up and was soon on the Internet searching its provenance.

Within ten minutes I had some solid information that told me I’d made a very special buy. Roopa is an Indian-born designer who’d had her own fashion label, Haldi. She left India to move to Melbourne, Australia, with her husband for his IT job. Roopa became inspired with the idea of bringing Australian aboriginal art into fashion that would be a far cry from the cheap cotton T-shirts sold to tourists. However, her interest wasn’t welcomed by gallery owners and artists. I mentioned T-shirts? Many indigenous artists have been exploited by Australians and others who copied their designs without paying them.

But Roopa had a vision of a business model that was different. I’m going to call it the Indian artisan model. Throughout India, there’s been a longstanding tradition of custom clothing making—and certain villages are known for a certain kind of block printing, or silk weaving, or cotton embroidery.

These niche technique are prized, and the regional artisans are celebrated by contemporary designers who ask them to do finishing touches such as embroidery around a neckline or hem. Mahatma Gandhi, who advocated wearing handspun clothing as a way of resisting the British in the early 20th century, would be smiling today if he could see the “desi chic,” “ethnic-cool and “modern handloom” fashions that are the rage.

The Fab India chain that sells clothes for all ages and sizes stitched from silks and cottons hand-loomed by people in rural communities. Also well-known are Anokhi and Cottons Jaipur, retail chains that specialize in fashion made from cotton woven, dyed and block-printed in Rajasthan. A high-end designer, Ritu Kumar, has spent the last quarter century collaborating with Kala Raksha, an organization in India supporting hereditary artists, and several other regional textile weavers and embroiderers. Last year in India, I was pleased to buy a Ritu Kumar kurti (woman’s tunic) with a meticulously hand embroidered placket typical of the Kutch region of Gujarat. But the coloration is subtle and works well with the modern printed silk fabric.

Back to the Australian-Indian collaboration: How could an Indian woman new to Australia convince aboriginal artists to work with her?

Here’s what Roopa did. She pledged to give credit where it was due. She offered put the artist’s name on each of her garments. Remember the mystery of two women’s names on my dress label? Here is Lily Hargraves, a “desert walker” in her nineties who’s one of Australia’s top aboriginal artists. Her paintings are exhibited around the world and sell for thousands of dollars.

Lily’s full name is Lily Nungarrayi Yirringali Jurrah Hargraves, although she’s most often known in art circles by the short Anglo name. She was born in the Northwest Territory in 1930 and having had a number of very hard jobs throughout her life, began painting in the tradition of her ancestors about thirty years ago. Lily is recognized as a senior Law Woman, which means she is an officiant of Waipiri indigenous culture—and her story is fascinating. And here are some of her paintings from the online museums and galleries in Australia. Looking at her work made me realize that’s a tree on the front of my dress.

Looking through Roopa’s designs since the 2012 collection that included my “Lily Blue Dress,” I’ve noticed that indigenous artist names are continuing to decorate the dress labels. Additionally, the design label is donating 20% of her profits to aboriginal groups. And the India connection also helps artists, because the silk is printed and embroidered in India at Roopa’s artisan workshop in Bangalore. The subtleties of clothing construction are overseen in India by Roopa’s co-artist, the acclaimed designer Sudhir Swain. The most recent collection—Resort 2018—was just shown in Australia a week ago and shows a riot of glorious abstract floral motifs merging with gauzy, gilded Indian silk.

Some might argue that fusing two cultures like this degrades the original. But fashion by its nature is an evolution.

Mahatma Gandhi told his followers a century ago what you choose to wear delivers power. Just this spring in Europe and America, women have been attacked for wearing traditional Muslim clothing items like the hijab and abaya. Given this context, wearing the textiles of international designers and artisans feels like another way to show resistance.