This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

As a teenager, I loved to read bodice rippers. That passion faded. I explain it this way: I grew up to be a mystery writer. Romance novels don’t hold my interest because the outcome rarely varies from my guess on Page 20.

I’m sure I sounded like a sourpuss when I declined my friend’s advice to watch a popular Netflix Original series titled “Bridgerton.” Executive Producer Shonda Rhimes’ show is based on the Bridgerton romance novels written by Julia Quinn. Quinn is a Harvard-educated writer who is a career romance novelist. In an interview with Collider, Quinn said she was not in the writers’ room for the show and considers herself just like the other fans when she reacts to the program.

Eventually, curiosity overcame my resistance. Especially because I knew there would be South Asian actors playing big roles in Season 2. One quiet evening, I made tea, donned my pajamas, and logged into Netflix.

Reader, I found myself captivated. Picture a London where Black, White and Brown elites dance, play sports, and dine together under the watchful eyes of (mostly widowed) society mammas. Men are the arm candy, and women the deciders, in this re-imagined world.

Lady Mary Sheffield Sharma is a British-born lady of middle years whose mother is Anglo-Indian married to a White British Lord. We learn from gossiping members of the ‘ton’ that over twenty years earlier, Lady Mary fell in love with an Indian man with unsuitable lineage who worked as a clerk. She left Britain married to Mr. Sharma and in India, and happily raised his daughter Kathani (called Kate) from his previous marriage to a wife who’d passed away. She also gave birth to a second girl, the petite Edwina. Things were good. Mr. Sharma clerked for a maharaja, and the girls grew up with palace manners, many languages, and lessons in music, dance, and hunting. The actors playing these characters are Shelley Conn (Lady Mary), Simone Ashley (Kate Sharma) and Charitha Chandan (Edwina).

After Mr. Sharma’s premature death, Lady Mary sells all she possesses for sea tickets to England so she can take the daughters to London for the season. Her step-daughter Kate refrains from putting herself forward as a candidate, because she’s fully committed to screening every man who shows interest in Edwina for social standing, kindness, and reputation. As Edwina’s romance takes off with the handsome young Viscount Anthony Bridgerton, Kate finds herself skeptical of his motives.

Bridgerton’s female-dominated marriage-brokering with an insistence on respect and love reflect 2022 values. However, the background story about Indians coming to Britain to marry actually holds truth. Starting in the 1600s, Britain’s East India Company sent ships filled with unoccupied young men to India, relative latecomers to the game of colonialism. They were following the pattern set by Portugal, Dutch, French, and Danish-Norwegian trading companies. These countries vied for the chance to claim ownership of land, and then profit from the agricultural and mineral riches.

Naturally, many of the bachelor employees paired up with local women: sometimes living with them, sometimes marrying them, and quite often fathering children. The slang phrase “Sleeping Dictionary” was sometimes used to joke about the ways these lovers taught language and cultural literacy to the colonists.

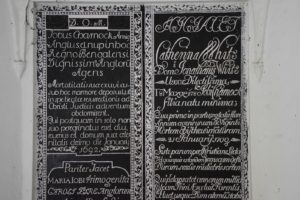

In 1657, Job Charnock was a young East India Company administrator who’d been promoted to a position as the Factor (trader) for Patna, a town in Bihar. Legend says that Charnock went on a day trip because he wanted to witness the act of suttee: the immolation of a widow on her husband’s funeral pyre. This misogynistic rite was practiced in some regions, particularly with elite Hindu families. Rather grisly sight-seeing; but then again, hangings and floggings were a public spectacle throughout Europe.

When Charnock caught sight of a young, beautiful woman going toward her death, he made a snap decision to rescue her. Renamed Maria, Leela was brought into Charnock’s world—where he rose to great heights in the East India Company and was credited for making the deal to get three villages that became Calcutta. Job and Maria may have had four children; some accounts say they were married. Bharti Kirchner’s novel, Goddess of Fire, uses history to imagine the romance within Job and Maria’s story.

More truth about East India Company men can be found in White Mughals by William Dalrymple. This is a deeply researched nonfiction work about the surprising number of British men who fell for Indian women and also preferred to live a luxurious Indian lifestyle. The book’s central story is of James Achilles Kirkpatrick, a British Resident in Hyderabad, who fell in love with Khair un-Nisa, a high-born Muslim lady. He married her and became part of the palace family, perhaps even working as a double agent for the palace against the East India Company. After Kirkpatrick’s early death, his two children were taken to England to live with their grandparents and denied further contact with their mother in India. They were baptized as Christians and given the English names of William and Catherine (or Kitty).

From the middle of the 19th century and beyond, Indian landowners and royals could extrapolate that the entire subcontinent was at risk of domination. Some maharajas tried to refuse the pressure to sell or gift land demanded by the East India Company’s officials. Often, a refusal to capitulate led to war, with the East India Company Army often, but not always, seizing land as their trophy.

When resistance to the East India Company’s actions became significant, Queen Victoria’s government formalized rule, sending to India a Viceroy who served in a prime minister-type role, with governors overseeing the various states, and political officers keeping a close eye on Indian royals who’d agreed to cooperate with Britain, in exchange for being allowed continued autonomy.

Now, Indian-British marriages were considered unacceptable, and people suspected of having Indian blood were often excluded from British-only hotels and social clubs. Unmarried White women from Britain sailed from India to marry the single British men working in India, and thus English families began to populate the landscape.

Yet Indians still sailed for England and Europe. A major draw was the chance for an elite education; a lesser-known reason was the loss of homeland.

Consider Princess Victoria Gouramma, who was born in 1840. Princess Gouramma’s father, the Maharaja of Coorg, fought unsuccessfully to preserve his South Indian kingdom. The East India Company won, annexing his kingdom to British India and making him a political prisoner. He eventually was released and applied for the right to take his eleven-year-old daughter for Christian schooling in England. The Maharaja’s true mission was to file a lawsuit against the East India Company for taking his kingdom by illegal means. Queen Victoria of England became Gouramma’s godmother and invited the child to live with the other royal children at Buckingham Palace. Gouramma was christened Victoria by the Archbishop of Canterbury. At 19, Gouramma married a 50-year-old British army colonel who absconded with her money and jewels by the time she was 23. She died shortly afterward of tuberculosis.

Queen Victoria also was charmed by Prince Duleep Singh, who, as a child maharaja, was coerced to give up his right to rule Punjab. Prince Duleep was separated from his Indian mother, Maharani Jind Kaur, who’d been Punjab’s regent since Duleep’s father’s death. Duleep was brought to England at the age of fifteen, where he was raised by a British official and his wife, educated and given a huge allowance. Queen Victoria also invited Duleep to stay with her, and she tried to arrange a marriage between Prince Duleep and Princess Gouramma. However, Duleep married Bamba Muller, a penniless but beautiful mixed Egyptian/German woman. They had many children at their mansion in Perthshire, and also many financial problems attributed to Duleep’s spendthrift ways. Prince Duleep’s lawsuit seeking his rights to rule to Punjab didn’t succeed, just as the Maharaja of Coorg’s legal efforts failed. But in his middle age, Duleep managed to return to India and reunite with his mother, who’d never stopped pining for him.

Not all royal travelers came to India against their will.

Maharaja Nripendra Narayan and his wife, Maharani Suniti Devi, were excited to leave the routine of life in the princely state of Cooch Behar for extended visits to England. Nripendra and Suniti hobnobbed with nobility and indulged in extravagant fashion. Their sons over-indulged themselves in the manner of British noblemen, with several following their father, the Maharaja, with alcohol-related early deaths.

The two youngest daughters from Cooch Behar, Princess Prativa (nicknamed ‘Pretty’) and Princess Sudhira (‘Baby’), were also often on these European jaunts. The sisters married British twin brothers (Lionel and Alan Mander). In Suniti Devi’s own Autobiography of a Princess, she writes that arranging these marriages was the proper solution because they would be considered unmarriagable by other Indian royal families.

As I consider the lives of these far-flung Indian travelers, it leaves a bad taste: a bit like Champagne gone flat. Inclusion in British life meant giving up so much of themselves. Nor could they be accepted for their changed manners if they returned to India, and sometimes, they couldn’t even enter the states where they were born. In many ways, their stories are a subtle echo of the much greater losses suffered by India itself.