This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

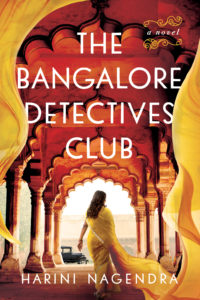

This week, I request the pleasure of your company for tea and conversation at The Bangalore Detectives Club. This ‘club’ is a gathering of sleuths who populate Harini Nagendra‘s dynamic historical mystery set in 1920s India. If you fancy the idea of tracking a murder mystery through a colonial city of “bungalows and banyan trees, lakes and monkeys,” your membership application is already approved—trust me, you will love this book. Harini was born and raised in Bengalaru (the post-colonial name for Bangalore) and was generous to give me her insights in the place, character, and history. Pour yourself a cup of tea and listen in.

Harini, I was privileged to spend a month in Bangalore in ‘old-ish’ days—the early 1970s, when I recall quiet streets shaded by lush trees and walks in fields with tall grasses. My sisters and I got to swim at a private social club that could have been the inspiration for the Century Club. Is there such a club that you researched—can you tell us its name?

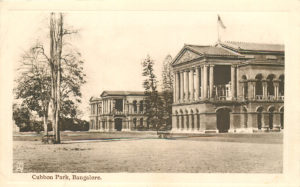

Bangalore of the 1970s was such a gorgeous city, isn’t it—with its tree-lined avenues, and open grasslands dotted with the odd large boulder, alongside lakes! The Century Club, where some of the opening events take place in the book, is a real place. My father was a member, and so was I for some years. We visited the club often, and I have woven some of the descriptions of the settings there from older memories. The history of the club which I present in the book is a true history. It was a place created by the influential Indian bureaucrat and merchant community so that they could have a space of their own to socialize, away from the other European-only clubs that excluded them.

I’ve heard you say that your protagonist Kaveri dropped into your life—she presented herself, and you tried a couple of ways of telling her story: first pre-marriage, and then married.

Sometime in 2007, I was in my mother’s home, reading up on some archival material on Bangalore for my academic research, when a young, spunky woman spoke up, made herself known and demanded I write a book about her. Being the fan of historical mysteries that I am, it seemed natural that I would write a mystery book.

Kaveri was initially not married. She was about the same age I have her at now—19 years—and I planned for her to meet her husband Ramu (they both had different names at the start) when he came to her home to give her tuitions in science and maths. But as I continued my research I realized it was highly improbable to have her be as old as 19 and yet unmarried at that time. Many young girls were married much earlier—by 12, or even sooner.

I changed things around, giving her the back-story of having been married at 16. In my mind, she was very much a young woman at the cusp of beginning adult life though, and I couldn’t have written her in that way if she had been married for three years—perhaps with a few kids—at the start of my book. Nor could I have begun a book written today, for contemporary readers, with an amateur detective who was 16. So I added another thread—while Kaveri and Ramu were married at 16, as many households did at that time, the marriage was a formality for some years. She continued to live in her parents’ home until she was 19, completing her studies as Ramu focused on his work. She then moves to Bangalore a short while before the book, starting life in another city, as a new wife, and with a fresh ‘career’ to develop as an amateur detective.

Kaveri’s in a situation with a loving, tolerant young husband, and his parents are holding power over both of them. Why did you choose this set-up, which actually gives her less freedom than if she were still unmarried? How does it intensify your messages about female empowerment and and also the mystery?

I heard my grandmother often say that women’s lives were a matter of luck. A young girl could be born in the most privileged of homes, and raised with the greatest of love and care by her parents—but if she then went into a home where she was treated badly, for the most part, her life was going to be blighted, and there was nothing much her parents could do to help her. Unfortunately this is still true of many women’s lives today, not only in India, but in many parts of the world. But the converse is also true. I know many strong women in my own family, and that of my husband, who flourished and made a strong impact in their own chosen areas, when in loving relationships with supportive husbands. For instance my mother’s grandmother, a home-maker married to a progressive bureaucrat in the late 20th century, was also an excellent herbal doctor and mid-wife.

Also, when Kaveri landed in my mind, she was always paired with Ramu—so marriage was a natural setting for me to choose. To help her sleuth in more freedom, I had to shunt her mother-in-law out of the way for much of the first book, of course. In terms of solving mysteries, pairing Ramu and Kaveri helps—while Ramu investigates the lives of men in the hospital, Kaveri talks to the women, and gets a very different perspective on events. And in doing so, she gets to explore how women in different strata of society lived, and were treated—thus helping the reader understand what an abstract concept like feminism might have meant to many different kinds of women in 20th century colonial India.

One of the ways Kaveri snoops at the bi-cultural, elite Century Club is by telling the manager she’s come to ‘take a cutting’ of some plants. Tell us about your background in ecology and how that shows up this novels settings?

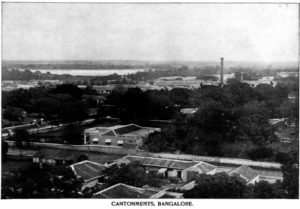

I have a PhD in ecology, and have been working on ecological research for 30 years now. Bangalore is one of my core focus areas, and my 2016 book Nature in the City: Bengaluru in the Past, Present and Future describes the ecological history of the city from about the 5th century CE to current times. This is a long, roundabout way of saying that I am deeply in love with, and perhaps even a little obsessive about, Bangalore’s ecology! The setting of the story, in Bangalore—city of bungalows and banyan trees, lakes and monkeys—was a very important part of my story. Through descriptions of the ecology of both parts of the city—the British colonial areas with their majestic rain trees and monkey-top buildings, and the Indian areas with their posh cottages and tiny mud lanes, with cows, monkeys and coconut trees—I hope to bring the contrast between the colonial occupiers and the native Indian residents into sharper focus. I also use ecology in places to heighten the tension, such as when a kite makes its mournful keening call while swooping down to grab a rat in its sharp talons, or when an owl, believed to be a harbinger of bad luck, hoots at night.

Writing about India under British rule is a balancing act. Rama Murthy keeps his interest in independence rather private because he’s being paid by the British government. Also, his boss, Dr. Roberts, does not fit the mold of how British colonial officers are portrayed. How do you look at colonialism and in what ways does this institution play into the mystery?

Colonialism is a background theme that has a dominant influence on the plot, setting, and characters: on every aspect of the novel indeed. It is a balancing act, and I love how you portray the collision of cultures in your Perveen Mistry series. Bangalore in the 1920s is not directly under the British rule but part of a princely state, governed by the Mysore king who is himself subject to British diktats and whims. As such the movement for Indian independence is somewhat more muted in Bangalore than it was around the same time in Calcutta or Bombay—but still strongly present, just a bit more in the shadows. There were some progressive British residents, just as there were regressive Indians—but overall, as a system, the power and control vested with the colonizers of course. Over the course of the series, as more time passes, I hope to show how the anti-colonial movement gained strength in Bangalore, and how Ramu and Kaveri’s own trajectories of growth intersect with and are shaped by these broader historical forces of change.

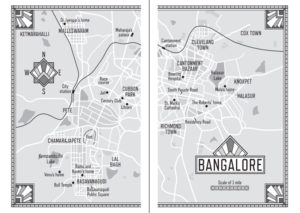

Your research is impressive, from the look into the communities of cowherds, the history of prostitution, as well as the reality of one of the few mental sanatoriums in India being in Madras. Tell us how you found the documents and other materials to help with this work. My favorite source of information is an old map of Bombay with the landmarks drawn right on it that I got from a UK seller on eBay. Do you have a favorite historic material about Bangalore that was useful?

Thank you! Since so much of my day job as an academic involves research on old Bangalore, I have masses of material to draw on, including gazette records, annual administrative reports, ledgers files that record obscure bureaucratic battles over lakes and cemeteries, and other fact-laden material. As a fiction writer, I needed to flesh this out to make the dry and dusty facts come alive. For this I used old maps and photographs, diaries and letters, biographies, and old stories told by people in my own family, as well as those of others whom I spoke to—including cowherds, fishermen and fodder collectors, and others who provided a glimpse into the parts of the city which are always left out of the archives. Maps were my favorite source of material too, though—I have a number of old maps of the city, but the one I love best is an 1880s map in the Mythic Society of India’s library, that is detailed enough to show the location of individual graves in European cemeteries!

I was excited to hear you mention in an interview some female family members in past decades who did brave things, like actually swimming in a sari. I also was impressed by the realistic detail you share about the rules surrounding a young Brahmin wife living in a traditional upper class family. What are some of the small rebellions you chose for Kaveri, and what are the ways that she stays in line?

The opening scene, where Kaveri goes swimming in a traditional nine-yard cotton sari, is indeed inspired by my husband’s aunt, whom I admire tremendously. Now 96 years old, she went swimming in a sari when she was a young girl, in 1930s Madras (now Chennai). Women in upper class families were fenced in by societal expectations and restrictions that dictated what they could and couldn’t do—to transgress some of these boundaries was to invite shame on the entire family, as you also describe so vividly in your books on Bombay. Sometimes women were the worst enforcers of these expectations, but at other times they helped other women find ways to circumvent these forced obligations, often in secret.

It is in the smallest of ways that rebellions often begin—a testing of the waters, so to speak. Kaveri longs to eat mushrooms, which, though vegetarian, are forbidden to her because of caste restrictions. She asks her maid Rajamma, who is also a confidante, to bring her mushroom curry, and eats it in the back of her home, hiding under a tree to escape her mother-in-law Bhargavi’s notice. She studies mathematics in secret at home for the same reason, because Bhargavi believes that too much studying makes a woman’s brains go soft—until she gets Ramu’s support, at which point she begins to teach other women like her elderly neighbour Uma aunty to read and write as well, expanding the opportunities that older women had to access books and reading material.

On the other hand, she does have to tread carefully not to lose the support of her husband. When she meets and befriends a vulnerable prostitute in danger, Ramu is furious with her, and forbids her from offering further help. But Kaveri doesn’t take no for an answer easily. Open defiance is not in her character. Instead, she works on Ramu, plotting in secret to bring him to her side.

The title “Detectives Club” makes me think of a group working together—aka a police unit, or even the Famous Five. Why use this term, and which characters do you see as being part of Kaveri’s mystery-solving in this book and others to come?

The collective strength of women has always been deeply fascinating for me. One strand of my research started in collaboration with the Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom focuses on how community collectives work together to conserve forests, lakes and other natural resources across the world. In The Bangalore Detectives Club series, I hope to show how women can come together to lift each other up, combat crime, and change society for the better.

I also love The Famous Five! I read and re-read every one of the series when I was young, and again when I introduced my daughter to them several years back. I think of Kaveri and Ramu’s crime-solving journey very much as a Heroine’s Tale, in the Famous Five mould, rather than a classic Hero’s tale. That is, it is a tale of collaboration and cooperation, rather than chronicling the lonely adventures of a single intrepid investigator. Kaveri and Ramu, Uma aunty and Inspector Ismail are the initial members of The Bangalore Detectives Club. Over time, as book two will show, the club expands to include some of the other characters from Book 1 such as Mrs. Reddy and Mala, as well as new characters that we meet along the way.

What’s the hardest thing about writing book 2—or is it coming as easily as The Bangalore Detectives Club?

I took 13-14 years to write book 1—because I didn’t have a deadline, and also because I was figuring out how to plot and write a full-length mystery novel and had to rewrite it and change the plot at least three times. With Book 2, I was on a very tight deadline. I do my best work when I am motivated by deadlines. That comes from sheer force of habit, a consequence of writing academic papers and popular non-fiction for 30 years.

But I also had the advantage of knowing a few things about my own process of writing: for instance, how to plot, what voice I should write in (I spent many months during the first book switching between first to third-person and back again). And of course I knew my main characters very well by then!

Book 2 is with my publisher, who is editing it as we speak. I found the start very intimidating. I opened my computer and then thought of the fact that I was attempting to write an entire book from scratch, and that seemed very foolhardy. But once I shut off that part of my brain and started typing out the opening scene, it flowed easily from there. Of course I still had to go back and edit the plot and text many times, but I knew that I would be able to get to the end eventually, because I had gotten to that end once before. Does that make sense? Of course I have no idea how Book 3 is going to be—this is a process of endless learning, and I’m sure there will be many obstacles along the way to navigate. I love being transported to a different place and time though, and absolutely enjoy the process of actually writing. Editing is hard for me though. I tend to get more impatient than I should, and I am learning to gradually put that impatience behind me.

Did the editors in your different countries (USA, India, and UK) ask you to change any particular thing to suit their audience (aside from spellings, of course)? I mean, did you have to provide cultural context for some publishers, or cut it back for others? Do you have any other foreign publication deals?

My UK editor, from Little Brown’s Constable Crime series, acquired world rights for my book, and the India version is published by Hachette India, which is part of the same group—so they used the same text. The US rights were purchased by Pegasus Books. Interestingly, they used the same proofed manuscript as the UK one, with the UK spellings! The UK publishers did ask me to provide a greater cultural context to explain some aspects, such as why Kaveri is vegetarian (because she is born into a specific community and caste which is vegetarian), or to explain unfamiliar words like lathi (bamboo stick), and provide a glossary. They also asked me to cut back in some places, such as when I got carried away with providing detailed botanical descriptions! But overall, they let me retain the cultural flavor of the book. I don’t have any other foreign publication deals at this point, but would love to, if there are international publishers out there reading this…

What’s the ecology field work you are about to undertake?

My husband and I have started to collaborate on some new research involving the Krishnarajasagara Dam in Mysore, which was built in 1910, and was one of the largest dams in the world at that time. Because of the pandemic, we have spent the past two years digging into archival material, and leaving the field work for later. We plan to spend the next few months making multiple trips to the dam, an associated hydro-electric station. and the agricultural landscape around the dam, including a power station. The Mysore kings were very keen on modernization, and Bangalore was the first city to be electrified in Asia in 1905. The dam, electricity, and the spread of sugarcane cultivation after the dam had a major impact on the region, its economics, ecology and politics which are visible even today, some 110 years later. We’re really looking forward to the field work; it’s been way too long since we got out of the city.

When can we next read a Kaveri Murthy book, and can you give a hint to the topic?

Book 2 in the series is titled Murder Under A Red Moon, where Kaveri stumbles across a murder during the darkly inauspicious time of an eclipse. Bhargavi, Kaveri’s fractious mother-in-law whom I conveniently sent away through much of Book 1, is back in Book 2. Will the two women mend their relationship, or will it get even worse? The background themes of feminism are even stronger in this book, which explores the rise of the women’s suffrage movement in 1920s Bangalore—and of course, the rumblings of discontent against the British colonizers continue to grow in intensity. Murder Under A Red Moon will be out in March 2023, and will have more delicious recipes at the back as well.

Reading through this interview, I learned so much about nature, the path toward women’s liberation in India, as well as the writing process. What a joy that Harini Nagendra has entered the mystery world and can enrich of all of us with her work!