This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

Back in Grade One—about the time I stopped having to use my finger to read word by word—I fell in love with stories. I could not get enough of reading, and thank goodness there were libraries to sate my appetite.

Libraries were the place I, as an elementary school student, could make my own choices about what I wanted to take home. It wasn’t like going to a department store, where my mom ultimately decided if she would pay for the sweater I wanted. I didn’t have to get permission; and it didn’t cost any more for me to take out nine books or one. It was all free.

I read so fast in those days I rarely was served with an overdue fine. My library in childhood was the Roseville Library in the Ramsey County, Minnesota, public library system. I still half-remember the kind librarian who thought I was lost because I was a ten-year-old walking very slowly the shelves teen section. I was glad she let me stay, because I really wanted to get my hands on every Rosamond Du Jardin romance on the shelf.

Almost all of us have public library branches in our towns, but this concept wasn’t an automatic right granted by city governments in the way that streets and schools and fire stations were.

Setting up a library was an expensive process, and in the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries gentlemen of means put in money to build libraries and stock them—and the borrowers were people of means who paid a subscription fee.

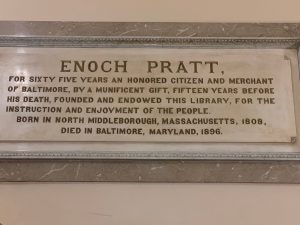

One of the most successful businessmen in 19th century Baltimore, Enoch Pratt, believed the city needed a “free, circulating library open to all, regardless of property or color.” His massive donation established a grand library that opened in 1886 with 32,000 volumes and an endowment of more than a million dollars.

I got my library card here after I finished college and began writing for the Evening Sun newspaper, which was only four blocks away. I spent countless hours here on research in the Maryland Room, or browsing old books for sale at the annual benefit, and often losing myself in the fiction section.

Did I ever imagine I’d have my own book in the Pratt?

No way. I thought I would always be a reader, not a reader-writer.

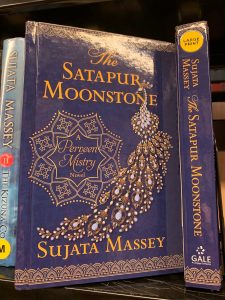

For the last twenty-two years, I’ve had the honor of being in the Pratt Library’s fiction section, in the M’s. I was there today and discovered the Pratt library has a book by me I didn’t know existed. No, it’s not pirated. The unusual edition of The Satapur Moonstone with striking blue hardcover is the LARGE PRINT EDITION.

Over the last forty years or so, the library’s grandeur slowly wore down. By that I mean the brass on all the doors dulled, the painted frieze going around the grand hall faded, and antique wooden furniture on the second and third floor became scuffed and dull. Due to increasingly limited funds from the state and city, such restoration was not in the cards for a library system struggling to stay open six days a week with enough money to pay workers and computer stations for users. Not to mention, the increasing costs of paper books, ebooks, and audiobooks.

A massive campaign to fund the library’s physician revitalization began under the visionary hand of the Pratt’s former CEO Carla Hayden (our current Librarian of Congress!). Heidi Daniel assumed the CEO role and is here to preside over the grand-reopening. I haven’t met Heidi yet, but I sense through her actions a commitment to making the Pratt Library a place where everyone feels welcome. We have another first—the Pratt is now one of the country’s first “fine free” libraries.

It is gratifying to see that in this restoration, the Pratt Central Library has not become a mausoleum or museum, but has revisioned some of the gracious spaces as special areas for people working on projects together. I saw doorways leading to large, open areas for teen-only activities and for fine arts creation.

A major focus of today’s library is assisting people in bettering their lives, primarily through finding work. There are daily workshops around the Pratt’s 22 branches to help Baltimoreans with job hunting, resume writing and issues of justice.

Recently, Baltimore Style Magazine asked me some questions about my work. They wanted a suggestion of where to take my photo, and the Pratt Central Library sprang to mind right away. The picture that appeared in the magazine has me virtually dancing through stacks. If you follow the link to Baltimore Style, look for the digital magazine and start flipping: I’m on page 54.

Here is how this fashionable escapade unfolded on the mezzanine level of a large city library. The Pratt’s PR, Meghan McCorkell, did a very professional job with these two photos she snapped.

I was back at the Pratt again today to renew my library card. The windows were full of gorgeous paper art commissioned for the opening. I hope these works are up for a long time, they are so gorgeous.

Once my card was in hand, I tooled around the building looking at an old world made new. I also needed a book for my writing, so I asked a social sciences librarian to bring up a particular book on police history that I’ve borrowed a few times. it’s not on the regular shelves, but in an underground (I think) archive.

There are some libraries that offer browsers access to the archive stacks—the Pratt is not one of them. I harbor fantasies of being allowed to wallow in these secret stacks, to see what other volumes on India I might fall in love with.

Do you have a library love story?