This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

Last weekend, when I was visiting the “Twin Cities” of Minneapolis and St. Paul, I was hit with an unexpected surge of purple.

Purple was the favorite color of Prince, a Minnesota funk-rock star—and April 21 was the one-year anniversary of his untimely death in 2016 by overdose. I grew up in St. Paul and was just a few years younger than the man born Prince Rogers Nelson. Prince released his first album, Soft and Wet, at the age of 17, and I avidly followed his every move over the next several decades, as did my sisters. Like Prince, we were young people of color living in a state that was predominantly white. There were no black musicians played on the radio except for on our sole “black” station, KMOJ-FM.

It was hard to make friends, or find someone willing to date you, when you were a few shades darker than the majority or had an unpronounceable name. It was exhilarating to see Prince—a small, light-skinned black man who wore lace and satin and high heels—fearlessly be himself.

Prince’s biggest local shows were at a large nightclub called First Avenue at the downtown Minneapolis. First Avenue remains one of the top national nightclubs that still showcases local performers. Prince’s first film, Purple Rain, is a fictitious story in which he plays “The Kid,” someone very much like himself, trying to make it in show business, get the girl, and deal with some hard family issues. The 1984 movie was a hit, with Prince’s artistry stealing the show. Watching it later, I notice how mixed-race his audience appeared. People seemed to forget about traditional boundaries and fell in love with his hypnotic beats and daring lyrics. I mark this as the start of a new Minnesota.

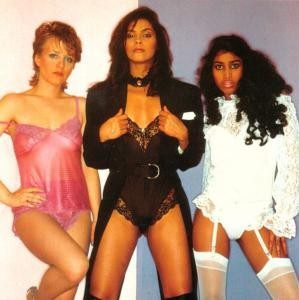

Prince shot to stardom shortly after I’d become 18, the legal age to go to First Avenue’s night shows. When he came to Baltimore’s Civic Center, I was a college student and bought a ticket to his show. I pushed my way to the edge of backstage and gave one of the roadies a note addressed to my high school friend, Susan Moonsie, who’d become a singer in one of his custom-made opening bands: Vanity 6. I was gloriously lucky to find myself escorted backstage, where I hung out with Susan all night and met the other Vanity 6 singers and the men of The Time. However, I didn’t get to exchange words with Prince. Susan didn’t want to introduce me because the two of them were in an argument.

Despite his superstar status, Prince never abandoned Minnesota. He built a massive home and recording studio in the suburb of Chanhassen named Paisley Park, after one of his songs, and often opened it to friends and fans who came for private parties with performances. Prince sometimes showed up to play at Minneapolis’s Dakota jazz club or First Avenue.

During Prince’s adult years, Minnesota diversified. The state became the chief home of refugees from Somalia. It became a leader in families with international adoptions and was said to be “the gayest city after San Francisco.”

Was Prince a symbol of civic change—or was he an agent of change?

I wondered about this as I walked through the Twin Cities last weekend listening to the top favorite 89 Prince Songs on The Current, a Minnesota Public Radio station that, like KMOJ, had a special relationship with the artist. Spring comes late in the upper Midwest—while the grass was green, the tulips were just popping and the trees were taking on a light haze of leaves. In many neighborhoods, the gardens sprouted yard signs: “Black Lives Matter,” and “Falcon Heights: The World is Watching,” a reference to the fatal police shooting of Philando Castile in my own neighborhood that came a few months after Prince’s death.

The most popular sign was in rainbow hues, with the state of Minnesota on one sign and on the other, the phrase, “All Are Welcome Here.” The overt activism reminded me of the growing political and spiritual content of Prince’s work in the years just before his death. He had his eyes on the world, and he wanted to keep building bridges.

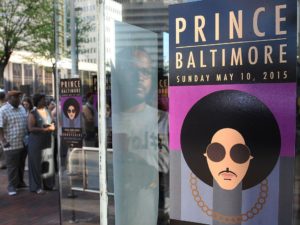

In April 2015, I was living in Baltimore during a period that it seemed one black male after another was killed by police. In Baltimore, a young man named Freddie Gray was arrested on suspicion of carrying drugs; he died after a short ride to jail in a police van. During a two-day period after Freddie’s funeral, areas of Baltimore were filled with destructive protestors and hundreds of fires were set. We endured almost a week of curfew and a city takeover by soldiers with the National Guard.

As the city was stilling itself, the city had stilled—but hardly returned to normal—Prince announced he was coming to Baltimore to perform a free “Rally 4 Peace.” He booked the Royal Farms Arena at his own expense. He wrote a song called “Baltimore” that was compassionate yet had a happy, bopping beat. The song will never be his greatest hit, but it seems a perfectly distilled essence of his style and dogged determination to share joy as the way forward.