This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

Political chaos is making me cling to quiet evenings home. As it turns out, I am not alone in thinking that our everyday, intimate life can be a source of restoration.

The idea that our kitchens should remain places of joy was explored beautifully on this Sept. 13 Splendid Table podcast. One of the show’s regular contributors, editor Tucker Shaw from America’s Test Kitchen, suggested replacing old spices with new ones as a profound way to nurture yourself.

A few days after hearing the podcast, I got an email from a home organizing site, A Bowl Full of Lemons, that proclaimed that very day was the one that everyone needed to purge their spice drawer. Yes. In that dream blog world, all the spices come in matching jars, and they take up one small drawer.

The writing was on the wall—or in my case, the kitchen blackboard. I hoard spices the way that shops and libraries store books. In fact, I believe in a library of spices, along with a library of cookbooks. But I knew that any spice organization program in my home would last much longer than the fifteen minutes suggested by A Bowl Full of Lemons.

I like to think that my own spice and dried herb trail is a microcosm of the original spice trails emanating from Asia and the Americas to Europe. In my house, one is forced to hunt down spices in both a kitchen and a butler’s pantry. The journey includes stops to view, sniff and taste many dozens of jars that have been crammed like unhappy subway riders in six kitchen drawers, with the overflow packed in three plastic containers in a large cabinet.

There are so many spices that our husband does not know where to start looking, when he wants to cook. His solution is to go to the neighborhood grocery and buy a tiny, six-dollar bottle of whatever he does not see.

I needed Marie Kondo, but she was not available. And predictably, as I began considering the values of my assorted spices, many of them tugged mightily at my heart. It is not the same as wilted celery from a fridge or frostbitten lamb from the freezer. The spices look fine, and they will not make you sick, if you add a tired teaspoon to your soup or stew.

But here’s my problem. Removing spices is striking at history of past cooking—and dreams of dishes that could be.

One of the first big jars I regarded was a giant one stuffed with dried purple-red guajillo chiles that I purchased at a bodega, probably around 2009 when I was very ambitious. The chilies traveled with me to Maryland in 2012—quite far, because we have lived in Maryland since 2012. The dried chiles are so large and gorgeous—but could they be a tad too complex for my ordinary enchilada and chili nights?

Probably a third of my spices hail from India. I adore a multi-spice pack from the southern state of Kerala brought to me by a relative a few years ago (who’s counting). The pack has locally grown black peppercorns, star anise, whole cloves, cardamom pods and cinnamon bark. This is a key, highly aromatic grouping that goes a long way, either as single elements, or roasted and ground into a kind of garam masala used for Malayali cooking.

Kerala is also the home of my most unused and mysterious item: cocum. Cocum are small sour black orbs that were a subtle flavoring in a fabulous shrimp curry made by Maria Zacharia for my daughter and me in her Alleppey home in 2008. Maria gifted me the cookbook she wrote, and because cocum was on the ingredient list for many of her fish recipes, I hunted it down in a local market. Despite the passage of time, the cocum is moist, and it is supposed to be soaked before cooking. It is staying with me another decade, I believe.

In my various drawers and the cabinet, I discovered three containers of the black cumin seeds more commonly known as nigella or kalonji. These were easy to toss, because I had already bought a new bag and discovered the taste of a new kalonji seed is biting and much more interesting than the aged seeds.

Taste-testing and careful viewing were good way to lead a reluctant drawer-cleaner to truth. Cardamom pods might look green and plump, but inside, if the seeds are white, they are far from fresh. I found that the cardamom I’d stored inside the butler’s pantry cabinet had fresh black seeds inside the pods, making it a snap to eliminate the three other small jars of old cardamom pods.

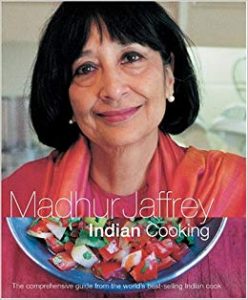

Spice mixtures are a special problem unto themselves. Anyone who cooks from a good Indian cookbook—and I am thinking most specially of Madhur Jaffrey—is instructed to roast and grind spices and mix them in particular ways for easy use in future dishes. The same kind of spice blend making is encouraged in Mexican cooking and Middle Eastern cuisine. It took me more than a half-hour a couple of years ago to make Madhur’s hot and sour chaat mixture, but I know that the purpose of making these spice mixtures is because the freshly ground spices are more fragrant than what comes from the store. Though I do not hesitate to buy spice mixes that are new to me, like a bruschetta blend I saw in a department store in Milan, or the Ras El Hanout spice blend I found in a Middle Eastern grocery store in Brooklyn.

It is fortunate my sodium level is normal, because my kitchen is packed with salt. We start with coarse kosher salt and finely milled sea salt, but the real adventures begins with the various flavors of Hawaiian sea salt that I brought home from Honolulu. My feelings run deep for silky gray smoked sea salt, Himalayan pink salt in both block and granulated forms, and kala namak, a volcanic salt from India. I was thrilled to find flaky Maldon salt from England at Trader Joe’s, so it’s been in my wheelhouse for a few weeks. I’m also working through various salt specialty mixes with flavorings of garlic, chili, ginger and paprika. Confession: I only threw away one small container. However, I have pledged not to buy another grain of specialty salt for the next three years.

Midway through the purge, my husband paid a call to the kitchen and requested that I go easy on our tiny collection of American spices (I secretly call them processed vegetable extracts). I am talking about dried, mechanically-minced or granulated or powdered garlic and onion. There is a role for them in some American Thanksgiving dishes and the foods of Louisiana. To each their own. At least their maker, McCormick, is a Baltimore company!

Salt is cheap, and other spices are very expensive. If I had to go to the mat to save a particular spice, it would be the two containers of Iranian saffron. Saffron is a very powerful spice: so aromatic that even a pinch goes a long way. At $160 an ounce, I am certainly going to keep using the precious saffron threads I have, especially with the political drama going on. Who knows when we can get fresh saffron from Iran?

After five hours of slow work, the drawers are cleared, and I have spare room in all of them. I also know exactly where to find what I need.

The epilogue to the grand clean-out is that I now have several dozen of empty glass jars and tiny meal tins. Some are going to recycling, and others will be washed and saved as containers for the small amounts of fresh spices that I intend to buy in the future. Because that was the point of changing out spices: to get the chance to absorb fresh, thrilling new tastes.