This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

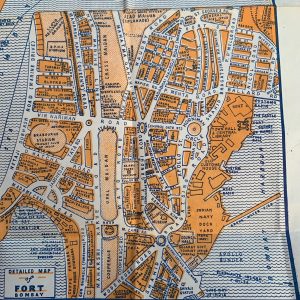

Lately, my work in progress has been dragging its feet. Maybe it’s because I’m writing from my home in Baltimore, while I long to revitalize myself with a walk through Fort, the historic Bombay neighborhood I write about in the Perveen Mistry novels. Even though I’ve been there in person, I feel like I need to be led along the streets again.

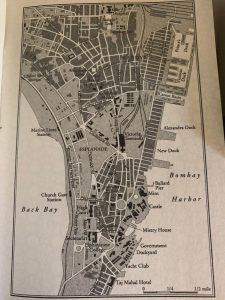

If I could step into an old map, it would fix everything, wouldn’t it?

Maps inside a book are like sugar in dessert. You don’t need it, but it’s so much nicer when it’s there.

My relationship with maps did not start out well. I used to be terrified of when my parents were driving, and we got lost. The driving parent would call out for someone (the spouse or eldest child in the car—yours truly) to study a large, cumbersome road map and discern the correct way back. It seemed I could never read the map fast enough nor could I orient myself in a direction other than the printed paper. Because of the way my brain processes direction, I was not a natural fit with maps—though I need them, because I have a terrible instinct for misdirection.

I began feeling less overwhelmed by maps when I lived in Japan. This was the era when I was a foreigner in Japan doing groundwork for a first novel. I wanted to write a mystery that felt real; and for me, that meant naming actual streets and train stations. The little line maps on the back of every shop or restaurant’s business card were my salvation in cities like Tokyo and Yokohama where many streets didn’t have names, just numbered buildings.

After publication of my first book, The Salaryman’s Wife, I learned how attentive readers are to details of place. If I located a known building on the wrong corner, I would hear about it. But just as quickly as people catch errors, they also delight in hearing the names for almost-forgotten places.

In India, many city and street names have changed due to political progress—and here I am, sounding like an old person, talking about “Bombay” instead of Mumbai and “Bruce Street” instead of Homi Modi Street. I search out the oldest-looking places and commit them to my camera, and my heart.

After independence in 1947, Indians refused to continue speaking of streets named for men who were the enforcers of its colonial past. Many city and street names on maps officially changed from English government officials to Indian heroes, although verbally, the English names are often still used in spoken directions by locals. Ironically, there is at least one area renamed after a British person: Horniman Circle. Benjamin Horniman was a progressive British journalist who was thrown out of the country in the early 1900s for writing supportively of Mahatma Gandhi. The handsome driving circle in South Mumbai framed by offices and shops had previously been named in honor of the 13th Lord Elphinstone, one of Bombay’s governors. If I hadn’t learned who Mr. Horniman was, I might have mistakenly misnamed the circle in my novel. Interestingly, there still is an Elphinstone College in Bombay (named after the second Lord Elphinstone) as well as Wilson College, named for the Scottish Presbyterian missionary educator who founded it.

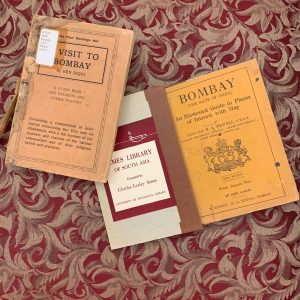

For quite a few years, I have been gathering such arcane details from old guidebooks and maps. Some of my key sources are huge, vintage reference books like the Imperial Gazetteers of British India, and old city guidebooks, especially if they have maps. The best place in the United States I know to find such wonders is the Ames Library within the University of Minnesota.

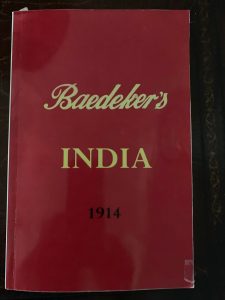

Karl S. Baedeker was the famous publisher of 19th and early 20th century travel guides that originated in Germany, a country with people still passionate about travel. The Baedeker guides were meant to help Westerners see marvelous places beyond their imaginations, all the while in comfort and security. Baedeker guides were often translated into English. However, Baedeker’s only guide to India was published in 1914, and due to hostilities between Germany and Britain, never found an English language publisher. Not until 1985 was the guide translated into English by Michael Wild. I was grateful to be able to buy the modern translation and picked up from it some interesting details about the city from an early 20th century German viewpoint.

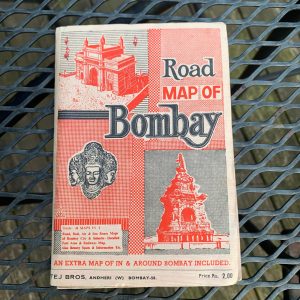

Because old maps are very helpful, I was tempted when I discovered a 1967 Bombay folding map being auctioned on eBay by a seller in England with a starting price of 49 pounds. Once airmail delivery was included, the map would run me about $77 US dollars.

I’ve bought moisturizers that cost more, but I hesitated. My worry was this mysterious map on eBay would be focused exclusively on tourism venues. I knew it also would have plenty of Indian street names, so I would continue to need to cross-reference street names.

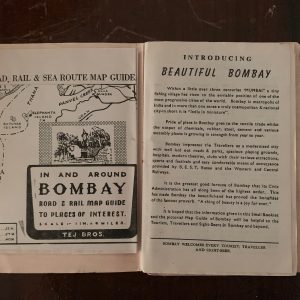

The seller had posted some photos of the map booklet that looked promising, so I pressed the button to bid. It was the last day of the auction, and it turned out I was the only person on earth interested in a Tej Brothers 1967 Bombay Street Map.

Two weeks later, a neat little package in a sturdy, waterproof envelope arrived from England. The map booklet had traveled safely between two pieces of cardboard inside the package. It was just the right size to put inside a handbag, yet it was utterly fresh, as if it had never been opened up and read. To say this map is in perfect condition is an understatement. Some of the booklet pages unfold into very large, easy to read maps which are rich in color and landmarks.

The booklet also has listings of popular name of restaurants and hotels, movie houses and shops. I can’t wait to show it to my stepfather, who was a young man-about-town during the map’s prime.

In the week that I’ve been studying it, the map’s provenance has intrigued me. Because there is absolutely no smell of mold or deterioration from moisture, I believe the map probably left India many years ago and was kept in a cool, dry location. I wonder: was the map’s first owner someone who meant to use it while exploring Bombay, but instead relied on the directions of a human companion? Or did the planned trip to Bombay get cancelled? Could it be the map never had a real owner, but just resided for decades in a travel agent’s file cabinet?

I’ve come to realize that a map can offer much more than geographic placement or inspiration for story; it can be a mystery unto itself.