This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

On a hot Saturday afternoon in early October, I was in the Mumbai Harbour, taking the slow tourist boat back from the cave temples on Elephanta Island. The water journey had been almost two hours, and I had only a few drops of water left in my bottle. I was overjoyed to spot a tall rounded red tower appear over the waves. I knew that if I could see part of the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel, I wasn’t so far away.

The Taj is a city hotel, but it was designed with its turreted front facing the sea, which was very unusual for 1903. The hotel’s sea-facing facade also offered its earliest guests a wonderful view from their bedroom windows. This philosophy of focusing on a guest’s views—rather than a hotel’s prestigious appearance on a cityscape—was a new way of thinking.

The Indo-Saracenic showpiece was conceived of and built at a cost of 500,000 Pounds Sterling. Not by the British, who ruled India at the time; by an Indian.

Jamshedji Tata, a brilliant Parsi entrepreneur, had the idea of building the Taj after a devastating bubonic plague epidemic in the 1890s caused many to lose faith in the city. He also created a nondiscriminatory policy of admission to all races, although some of the city’s best hotels and private clubs in the city prohibited Indian entry. He named his hotel after the spectacular historical tomb in Agra, the Taj Mahal, knowing it conjured exquisite beauty in the minds of tourists.

The rooms, restaurants, halls and Turkish bath were spectacular. The hotel was the first building in Bombay to have electricity in the rooms and electric lifts imported from Germany. The Taj Hotel became the icon of fine hospitality in a country already world-famous for its hospitality. Interestingly, the chefs were French because even though the hotel’s owner was Indian, local dishes weren’t considered sophisticated enough. He also made sure to hire butlers and desk clerks who were European.

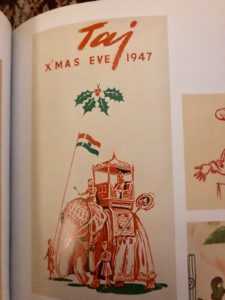

When India became independent in 1947, a Christmas Eve menu cover showed a maharaja atop an elephant, with a groom holding the green, white and saffron flag of the new democracy. It’s a strategic image that recognizes the importance of the hotel’s past royal customers who had agreed to join with the new nation rather than keep their former princely states separate.

For people who live in Mumbai, the Taj is mainly about meeting for meals, attending weddings, and shopping in the arcades. I’ve met more than one married couple who got engaged in the hotel’s Sea Lounge. My stepfather fondly remembers delicious lunches with friends at the hotel during school holidays. My mother, who’s been traveling on vacation to Mumbai with him for thirteen years, has a friendship with a charming elderly jeweler in the Taj’s shopping arcade… it’s impossible for her to leave the Taj Hotel without something sparkling in a small velvet bag.

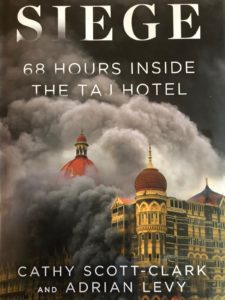

The Taj’s glory was almost its downfall. When ten Lashkar-e-Taiba terrorists from rural Pakistan targeted 12 sites in Mumbai on November 26, 2008, four young men raided the Taj intent on killing international guests, Indians, and staff. This mass attack also included the Trident-Oberoi Hotel, the Chhatrapati Shivaji train terminus, Cafe Leopard and Chabad House. The terror in Mumbai lasted 68 hours and resulted in 164 civilian and police deaths, with more than 300 people wounded. Nine of the terrorists were killed during the police response, and the one man caught alive was hung a few years ago in an Indian prison.

The siege of The Taj was the longest of all the battles during the 26/11 attacks. Twenty-two staff perished, as well as fourteen guests. Yet more than 300 guests were saved by the Taj staff, who stayed rather than evacuated.

I think there are a number of reasons for this. The motto for the hotel is “Guest is God”; I’ve heard it when I stayed at another Taj property. Also, the Taj training for staff is reputed to be quite intense, with people taking great pride in their relationship with the hotel, many of them hoping for lifetime employment. And these employees know the huge hotel’s layout. It is a a complex labyrinth with many interior elevators and storerooms added over the years. There is even a private club, Chambers, that was not marked on tourist maps. This is where many of the guests led by staff from public spaces waited until police arrived. Other guests who had been relaxing in their rooms hid in place for days until firemen could put ladders to the windows and bring them down. This was a complicated process, because not only does the hotel have a six-story historic main structure, but there is also a modern high-rise tower.

The Taj was secured by the police on November 29, utterly devastated by gunfire, with many areas burnt from grenade explosions and fires. Yet less than a month after the attack, the hotel re-opened for business.

In January 2009, I was in Mumbai on vacation with some family members. It was six weeks after 26/11. We stayed at our usual home-away-from-home, the Royal Bombay Yacht Club, just around the corner from the Taj. On the last night of this wonderful trip, we had a light dinner at the Taj’s Shamiana coffee shop, which sits near the hotel’s main entrance. Looking around, we saw the Taj’s rebuilding had been swift and was immaculate. A monument with the names of the hotel’s martyred employees was already erected in the lobby. We learned that the Tata Company, the original family business that still owns this hotel, pledged to pay college costs for all the slain employees’ children and would give their family members who’d lost breadwinners support jobs. The hotel had also paid for damages suffered by many freelance souvenir sellers in the area who lost business for months after the attack.

The goal of Lashkar-e-Taiba might have been to kill the Taj Hotel and other places that invoke the spirit of Mumbai—but that did not happen.

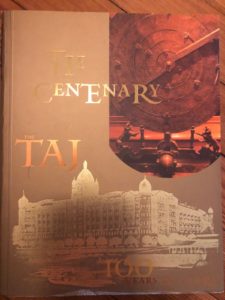

As the ten-year anniversary of the Taj’s triumph over terror approaches, I’ve been revisiting the Taj long distance. One way is through a suspenseful true crime book published in 2013: The Siege: 68 Hours Inside the Taj Hotel by Cathy Scott-Clark and Adrian Levy. I’m also delving into the Taj’s happier, older history in the form of a 415-page anniversary magazine, The Centenary Taj: 100 Years of Glory. This magazine, published in 2003, is the source of the charming photographs of old advertisements and Taj interiors that I’ve shared in this blogpost. Look for the whole magazine at antiquarian booksites, if you want a picture of Bombay history, art, food and culture.

My connection to the Taj Mahal Palace continues through my books. In my 1920s Bombay series, protagonist Perveen Mistry is a young woman lawyer whose grandfather was friends with Jamsetji Mistry when the two old Parsi businessmen were alive. Perveen’s family’s pre-engagement meeting with a groom’s family is at the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel!

I won’t tell you how that engagement turned out, but Perveen must return to the Taj again in Book 3, when dangerous riots make travel home impossible. Who knows, maybe I’ll sleep over one night, too.