This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

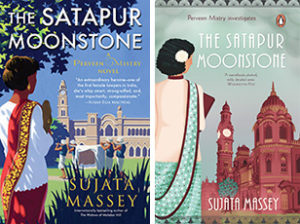

I’m thrilled to share the news that The Satapur Moonstone is finally in bookstores. My newest mystery novel was released last week as a hardcover in the US from Soho Press and as a Penguin India paperback for the Indian Subcontinent.

This is the second Perveen Mistry novel in the new series I am writing. In this adventure, Perveen takes a long, convoluted journey through mountainous jungle to investigate the living conditions of a young maharaja… and uncover the truth about the suspicious deaths in his family.

I am journeying through the United States to talk about the book, and while the airplane rides and freeway drives seem quite long, when I remind myself of Perveen’s exhaustive travels in 1921 India, my life seems pretty easy.

Perveen, who is a young solicitor working in her father’s law practice in Bombay, starts her journey to the Western Ghats with a train ride to the hill station of Khandala. From there, she is surprised to find herself the lone passenger in the back of a horse-drawn postal cart, tumbled among musty sacks of the Imperial Mail. A few days later she’s gingerly riding on horseback, and after that, she’s forced to recline in a short-roofed palanquin, a wooden box set on wooden poles that is carried by men for more than twenty miles through the hilly terrain to the palace. Believe it or not, when I visited the hill station of Matheran to research The Satapur Moonstone, I saw palanquins lying by the edge of the path, waiting for 21st century customers.

Rich foreigners being carried on the shoulders of poor locals is one metaphor for colonial rule. Perveen is against colonial rule, but in this novel, she finds herself taking a job for the government. She is well aware the British who’ve given her this temporary position as a legal investigator want her to make a decision that’s beneficial for them. While almost half of the subcontinent was territory governed by maharajas and nawabs, these rulers were considered princes of the Empire required to be loyal to the ruling British monarch.

Just as Perveen stopped to rest in a dak bungalow, or traveler’s rest house, I have recharging points: bookstores. Many of the independent mystery bookstores I’ve visited have dogs in house, just as the dak bungalows did. While the dogs in colonial India guarded people who felt vulnerable away from the city, bookstore dogs have a different role: making customers fall in love with them and go crazy buying books.

Back to Perveen’s trip! Our intrepid heroine arrives after a day’s travel to the palace. She is sore from a palanquin accident and sopping wet from rain only to learn there’s more than just a prince to worry about. She discovers that two maharanis living there are locked in a private war over the with each other, and the maharaja’s smart younger sister is being completely overlooked. What about their lives? Can her legal investigation change things for them and the future of Satapur?

When I write books like this, I strongly desire to write socially-just endings—yet I am mindful that my solution must be a realistic outcome for conventions of the time. A solicitor bound by rules of British common law, Parsi law, and other religious codes, knows this well. Perveen also isn’t the type to shove her decision on any client.

Perveen soon understands why the royals are stressed (a word I can’t use in the book, because it wasn’t invented yet). In the British Empire, Indian royalty were rarely allowed to choose where their sons were educated and what jobs they took after their studies; the British liked to handle that, in order to make sure the royals didn’t become too smart or independent. The British resident attached to a princely state also helped select brides for the princes, and they held the power to grant or deny a prince the freedom to leave India.

I spent about a year-and-a-half writing this book, so it cracks me up to learn some people have already read the whole book in less than a day. I am always curious to hear what readers liked and didn’t like about this book, and where they would like to see Perveen go next. When I spotted some women going into a bar in Houston carrying my book, I descended on them to find out.

Shared journeys are the best. And although my book tour of the US is undertaken alone, any feelings of loneliness disappear when I enter a different bookstore every evening, readying myself for unexpected questions and conversation.