This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

When times are frightening, worry comes easily. It’s much harder to be the one to step forward into harm’s way.

Recently, my attention was drawn back to World War II and one of its greatest heroines, aka the “Spy Princess.”

I am thankful for what she did—and I wish more people knew about her.

Noor Inayat Khan was born in 1914, with a background that feels uncannily familiar to my own. She had a father born in India, and a mother from the West. A cross-cultural marriage at that time seems unlikely—but it really occurred.

Noor’s mother, Ora Ray Baker, was born in Albuquerque, New Mexico. At age 20, Ora Ray attended a lecture in San Francisco given by Inayat Khan, a musician born in Punjab in the Sufi dervish tradition. Ora asked him for an interview, and the two fell in love and married. Inayat came from a fascinating lineage: his own father was Maula Baksh, founder of a famed music academy in Baroda named the Gyanshala, and her grandmother was Casimebi, a descendent of Tipu Sultan, the Muslim ruler of Mysore who died fighting the British in 1799.

The daring young couple married in London, and Ora Ray took the Muslim name of Amina Sharada Begum and began dressing only in sari to show her enthusiasm for India. She traveled the world with the musical group that Rahmat Khan founded, the Royal Hindustan Orchestra. Their eldest child, Noor, was born on January 1, 1914 in Moscow. After the outbreak of the Great War, the family fled to England. During their years in London, Inayat performed for both Mahatma Gandhi and Indian soldiers convalescing in hospital—as well as for grand opera productions such as Lakme that capitalized on the European interest in the Far East. Inayat came under government suspicion due to his connection to Gandhi and his skill at establishing Muslim and Indian community groups in Britain. He was seen as a risk to the stability of the British Empire. So in 1920, the family shifted to Tremblaye, France, so the musical group and other activities could continue without as much surveillance.

Noor grew up with interests in poetry and mysticism, as would seem natural for someone with such a creative family life rooted in the Sufi tradition. Her happy life changed in 1927, when Inayat Khan traveled back to India to see his family, and fell ill and died in Delhi. So it was under tragic circumstances that the fourteen-year-old Noor had her first visit to India in 1928, to pay respects along with the rest of her family at Rahmat’s tomb. Now she had to be the mother leading the family in their existence in France, because her grieving mother retreated in to a life of seclusion. Their Indian uncles living in France supported them financially. Noor played sitar, piano and harp; but she also had the gift of story. After attending a French university, she began a career writing children’s stories and translating Indian stories into English. Then the Germans invaded France. Their way of life had ended. This was a watershed moment for the family who had grown up believing strongly in nonviolence. Would they aid the British, who had been the enemy of their father?

Noor understood the the danger of the Nazis. She and her brothers felt called to support the resistance, and they decided the best way to do that seemed to return to England and offer their service. Here she used the name Nora Baker to fit in with the other women workers and not attract suspicion due to her half-Indian heritage. The story of her childhood and the challenge she faced is well-described in a biography by Shrabani Basu. A PBS documentary-drama, “Enemy of the Reich,” is another take on her story.

Noor was one of the first women radio operators trained in Morse Code—and decoding messages for the government could have been the extent of her work, save for one fact. She was a fluent French speaker, and that attracted the attention of the office of the Special Operations Executive (SOE), the famed espionage organization set up by the British to sabotage Nazi operations in Europe. Noor was interviewed by Selwyn Jepson, the British crime writer who became the SOE’s chief recruiter. Jepson asked if she would be willing to travel back to France and transmit messages. He said she would not be protected by international laws of warfare, and only receive ordinary service pay that would be held for her in England and given to her upon return—or to her survivors, if she didn’t.

Despite the dangers of the job, Noor immediately agreed. While Jepson felt confident about her, other men in the SOE were concerned that perhaps she was too naïve and honest. Her own father had taught her that the worst sin was to lie. While in training as an agent in Britain, she spoke to a police officer who stopped her and said she was in the SOE—a major mistake. She was counseled and allowed to continue, in large part because her speed and skill at transmitting messages was top notch.

Noor parachuted into France in 1943, clinging fast to the 30-pound suitcase carrying all her transmission equipment and false identity papers naming her “Jeanne-Marie.” Her codename, “Madeleine,” was one she chose from the stories she wrote. Just like her own mother—she had changed identity. Noor’s first action was to unite with the spy network, Prosper, to which she was assigned; but within a week, all of the members of the group were betrayed and arrested. The rookie espionage agent was on her own. The London office ordered her to return—but she refused, saying that since she was the only information conduit from Paris, she would stay until a replacement came. The government knew her capture was inevitable, but saw her act as the sacrifice of a soldier in the line of duty.

“Jeanne-Marie” worked hard sending messages and running from one part of Paris to the next, evading capture several times. She was doing the work of a six-person group alone. She communicated with a small group of French agents as well as the British. Some of her achievements during her first four months of work were identifying places for British to drop arms, assisting agents in getting out, managing distribution of arms, and insuring the escape of 30 airmen who’d been shot down in France.

The Germans knew of her existence, so she began changing her hair color—first to red, and then to blonde—and went back to the old neighborhood where she’d lived as a child. Former neighbors were willing to take her in, despite the danger she posed.

With the frequent captures of agents all around her, she must have known how close she was dancing to the fire. One day, she went to meet Canadian agents per London’s directions; the problem was, the Canadians had been captured and the people she met were non-German Nazis. Noor worked unknowingly with them for several weeks, but she was ultimately arrested and questioned in a Gestapo interrogation prison set up in an elegant mansion at 84 Avenue Foch. Unfortunately, it took quite a while for the British to understand she’d been captured—they kept sending messages on the radio, and the Germans answered using false information.

Other people held at the same time said that Noor resisted giving information even under torture. She attempted escape at least twice; in the end she was kept in solitary confinement and shackled. I can only imagine how dispiriting this must have been, and I wonder if she turned to the prayers and songs of her childhood for comfort.

The war had definitively turned in the Allies’ favor in September, 1944, and it became crucial for the Nazis to eliminate imprisoned agents who might later reveal their actions during the war. Noor and other women resistance agents were transferred from France to Germany and the Dachau concentration camp in Germany. There, Noor was identified as an especially dangerous type—they called her “the Creole” and was given the most sadistic treatment. She spent her sole night at Dachau being kicked and beaten and was ultimately shot to death along with the other women agents. It was September 13, 1944—seven months before the camp was liberated by the Allies.

Noor Inayat Khan was just one of many women working against Hitler who were killed in the line of duty. She is popularly called her the “Spy Princess” due to the long-ago link to Tippu Sultan, although she was by no means a royal.

Noor never was able to see her family after leaving England for France in 1943—and she certainly didn’t get the service pay the British government promised for her service. But she was one of three SOE women awarded the George Cross, and she also received the French Croix se Guerre.

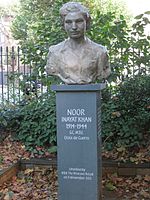

Five years ago, the British artist Karen Newman sculpted her image. Her likeness stands in London’s Gordon Square near her former childhood home. Fortunately, it does not say “Spy Princess,” a title she would never have been called, had she lived. Noor’s face holds a quiet, melancholy expression—as if she knows this, too.