This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

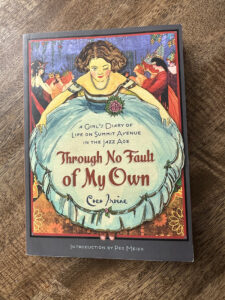

What would it have been like to be a mischievous teenager, living in your parents’ mansion in St. Paul, Minnesota, during the roaring twenties? It sounds like I’m talking about an escapist YA novel. The truth is, the 1927 diary of such a girl exists. To my great fortune, I stumbled onto a newly published version of a year in the life of Clothilde “Coco” Irvine while I was enjoying a short stay on Summit Avenue in Saint Paul, Minnesota. I bought the published book in the gift shop in the James J. Hill House, just up the road from her old home, which is now where the Governor of Minnesota resides.

During my time in Minnesota, I was struck by how below-the-radar fabulous it is. Minnesota is regarded by the most of the U.S. as a flyover zone. But the truth is, it was a major player in the development of cross-country commerce, thanks to the Mississippi River, and the railroad empire built by St. Paul resident James J. Hill.

When I was a child in St. Paul, Summit Avenue was always an intersection I passed through on the way to the airport or a good restaurant or bookstore. This time, I got to drive its full four and a half miles, and the farther east I traveled along Summit, the closer I got to the Mississippi River and St. Paul’s origin story.

St. Paul started off as the home of Ojibwa and Dakota people, who lived along the Mississippi River for an estimated 12,000 years. Fur trappers from France and French Canada traveled into Mini Sota Makoce in the 1600s. As Minnesota became a territory under the control of the United States, the importance of the Mississippi River for transport of goods outplayed fur. After treaties were signed in 1851, most Native Americans were forced out of St. Paul, as well as Minneapolis, and the Anglo transformation began. The name came from a Roman Catholic missionary who expanded a rudimentary Catholic chapel first established on the bluff into a church, later the St. Paul Cathedral. In the Cathedral Hill neighborhood, of which Summit runs like an elegant, wide artery, showcasing extravagant Victorian stone and brick homes built for the families of James J. Hill, Frederick Weyerhauser, and many long-forgotten lumber barons.

Summit Avenue had its start in the 1850s, but its magic moment arrived in the 1880s and lasted through the roaring twenties. During this time, so much money flowed that architects and skilled artisans emigrated from Germany and England to assist socially mobile homeowners wanting a special touch of class.

Coco Irvine Moles (1914-1975) grew up at 1006 Summit in a wide Tudor-style brick manor. In 1910, when Horace Hill Irvine, a lumber baron, had the house built for his six-person family, this section of Summit was still mostly open land. Yet soon the family was surrounded by neighbors. On nearby Grand Avenue, there lay the temptations of bustling urban life.

Coco was frequently called incorrigible by older family members and teachers. In her diary, she pours out her upset about the reactions she gets from her elders, although she was wildly popular with other kids. She especially got into trouble with her older brother Tom. One hilarious escapade was when they hid under a draped table on the family porch in order to run garden sprinkler water on all the guests’ feet. And there was a night that Coco and Tom sneaked out to go dancing at a nightclub. Before leaving the house, Coco dressed to the nines in her mother’s clothing and applied heavy makeup. There are many more “just between us” recountings, including a dangerous capsize while sailing on White Bear Lake, and kissing games.

Despite her charmingly written diary, Coco never became a professional writer, or did any sort of work. She graduated from Vassar and married well. Yet in the book’s afterward by Peg Meier, we come to understand the hardships she endured in adulthood. I wish she’d finished Vassar and become a writer instead of jumping into marriage. Or done both!

One very famous writer who did just that also grew up along Summit Avenue during the same era. I’m talking about F. Scott Fitzgerald. Fitzgerald was born in St. Paul, moved away briefly to New York, came back at the age of eight and grew up in his grandparents’ house on Laurel, which intersects Summit. He also lived in a rented gothic brownstone at 599 Summit after finishing Princeton and his World War I service. Here he wrote his debut, This Side of Paradise, which was published in 1920 and became a bestseller. It features scenes in the University Club, also located on Summit Avenue, and describes the adventures of rich young people socializing in clubs and along the frozen lakes in winter.

One of the few homes open to the public on Summit is the James J. Hill House. My third day of the visit, I walked five minutes from the Davidson and through the open gate to a Richardsonian Romanesque mansion which, at 36,000 feet, once was the largest residence in Minnesota. Before the Minnesota Historical Society got it, it had been gifted by the Hills to the Catholic Archdiocese. Because of that previous status, it’s devoid of most of the Hill furniture, and also had to be refurbished. Most of the Hill family’s furniture is in the homes of its descendants, not here. Still, it was a fascinating tour showing off splendid architecture and artifacts that gave context to Minnesota history and the Hill family’s rags-to-riches saga.

A grand dining table that is original was laid with old silver-plate sourced from Goodwill. It’s a good thing it wasn’t sterling, because a dessert spoon recently disappeared during tour hours.

I was happy to see James J. Hill’s desk from his St. Paul office was placed in the house. Of modest size and materials, it was nonetheless the place from where a railroad empire grew.

Large, grand, and comfortable digs of this size cost about $991,000 in 1891. Naturally, such a home’s maintenance required a large staff of servants. During winter, 2 tons of coal a day were delivered to feed the furnaces, and there were other lavish innovations such as huge blocks of ice delivered regularly and set into the walls of chambers to ensure refrigeration, and an elaborate security system to foil thieves. If you’ve watched The Gilded Age miniseries, you can see many parallels between the show’s Russell family and the Hills.

I stayed at the Davidson Hotel located at 344 Summit. The building, pictured below, is a stately golden brick manor built at a cost of $40,000 in 1915 for Watson Davidson, a farm boy who expanded his family’s small real estate holdings by purchasing commercial property and agricultural land in the United States and Canada. Watson married Sarah, the daughter of a steamboat commodore who himself had made a fortune operating more than 50 steamboats in the upper Mississippi. The couple had five children. After the Davidsons moved on, their house went through several incarnations including serving as an arts college. Although it’s now a hotel, it’s run in the style of an Airbnb with management reachable by phone, rather than in person, and entry to the house and one’s suite by passcode. You could almost pretend it was your own house.

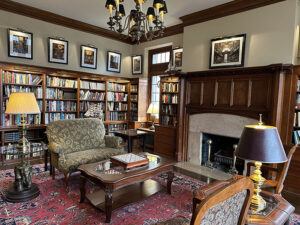

The mansion is vast, with an imposing wide, curved wooden stairway. There’s an elevator, but a sign that says “No Riders.” The grounds outside are in the midst of renovations, although the house’s interior is immaculate. The ground floor boasts a beautiful library filled with vintage books, games, and antique furniture. The house itself has been divided into eight suites, all with private bathrooms, and some, like mine, with a sitting room that had sweeping views from the bluff over St. Paul and the Mississippi River.

The great number of mansions on Summit Avenue have largely been preserved, thanks to the work of old-house lovers taking on massive projects, and the area’s listing as a Heritage Preservation District. Yards were dated with SOS signs, and when I asked a resident about them, he explained that the city wants to build an elevated lane down the center of Summit for bicycle traffic. This is despite the fact that wide designated areas of the boulevard already are marked for biking traffic. Adding an elevated cement lane in the boulevard’s center will force the widening of the street and cause tree loss, perhaps up to 60 percent of the street’s beautiful canopy. And it could also cause accidents, which goes against the objective of the city.

I had only been on Summit Avenue for a few days, but I wanted to save it. I wrote about a number of reasons in my letter to the city of St. Paul, but there’s also a more selfish reason. Old-fashioned places are vanishing at a fast clip. The longest stretch of Victorian architecture in the United States is something to hold precious for everyone.

Just a THANK YOU for your novels!

Discovered Rei Shimura back in the early 2000’s and really enjoyed them. Was disappointed when I couldn’t find any more.

Then, I saw your name again on something called THE WIDOWS OF MALABAR HILL. I bought it and not only loved it, but was THRILLED that you had not abandoned writing! I also thought it was pretty cool that you live in Baltimore, as I’m in Virginia, just across the river from DC.

I am about to begin The Bombay Prince and have pre-ordered Mistress of Bhatia House from my local tiny, and struggling independent bookstore. Being retired, I tend to use the library a lot, and will continue to. But now I’m also committed to buying books from them. With all that’s happening around books these days, we can’t afford to lose a bookstore.

So THANK YOU, THANK for your VERY enjoyable work!