This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

Last weekend I stood with forty women and a few good men in a training maneuver called a “Hassle Line.” We’d just enough time to share our names before we began playing our roles. My partner in the opposing line, a social work student named Faye, played a Donald Trump supporter. I was an activist the Women’s March on Washington, just trying to get along the Mall, with Faye harassing me.

We were practicing how to defuse confrontation, because it’s likely that some of the estimated 100,000 peaceful demonstrators will be heckled by sideliners or people wishing to cause destruction.

Faye and I tried to mix it up, but the fact was, we were too polite by nature. Although one of the best comebacks to hurled abuse proved to be: “Hi. And how are you today?”

With so many passionate conversations going across the Hassle Line, our Peacekeeper Training made quite a racket. That much much noise was unusual for our location, the Stony Run Friends Meeting House in North Baltimore. Members of the Society of Friends, also known as Quakers, worship in silence. I’m a longtime member of Stony Run, which grew out of Baltimore’s original Friends Meeting established in 1785.

Gary Gillespie, our training leader, was introducing us to Strategic Nonviolent Conflict, which is different than nonviolence, which has a reputation for passivity. SNC is a philosophy that regards nonviolence as a strategy because its thought to be more likely to work than violence could.

Gary is a Quaker member of Homewood Friends Meeting who serves as the executive director of the Central Maryland Ecumenical Council, a group of Baltimore Christian organizations working for social, economic and environmental justice. He’s been protesting since the Viet Nam war and has a very calm approach. He reminded us that when engaging in activism, it’s important to still have fun with each other.

By then, we had started to smile. The group that came had a wide variety of backgrounds, but it seemed to me that we were all concerned about the future of the environment and people in our country. Many women said the January 21 March would be the start of more political activity.

I signed up for the Women’s March because I want to make a public statement about my commitment to fighting for human rights. I didn’t think the march could do more than grab headlines for a day. But at the Peacekeeper Training, I began thinking our March has longer legs.

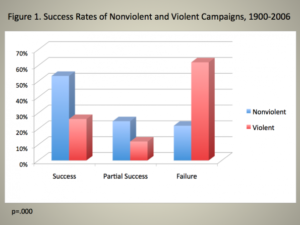

Erika Chenoweth, a Denver University professor of international studies, entered her field skeptical that nonviolent movements could succeed against big guns. When she collected data on hundreds of uprisings from 1900 through the present, she was stunned to see that that nonviolent protests and diversionary civil disobedience succeeded twice as often as violent uprisings. Nonviolent civil disobedience often includes women and children and thus was more representative of the whole society and was accepted by more people. Her research proved the tipping point for success in a people-led movement involves just 3.5% active involvement. In the U.S., that translates to 11 million people.

At the training, we watched Erika’s Ted X Talk in which she spoke about the value of large demonstrations. Apparently, large events provide an entry point for risk-averse people to become engaged in a movement. People naturally feel safer in numbers. When many citizens are drawn to a march, it almost guarantees key players will join the movement: educators, security forces, civilian bureaucrats, and the business elites. And as far as the other side goes, the officers serving in a bad government regime all have family members. Some of these may become protestors—and that makes the ruling party less likely to shoot.

A couple of the best-known recent successes in nonviolent protest are the Filipinos who deposed dictator Ferdinand Marcos, and the Serbians who ended the regime of Slobodan Milosevic. And not every nonviolent protest succeeds. Consider the Tiananmen Square massacre in China, and the current bloodshed in Syria. However, Erika Chenoweth thinks the Syrian opposition movement didn’t have enough time to plan their campaign; it didn’t turn into Strategic Nonviolent Conflict.

At the Women’s March, I’m sure there will wonderful signs and political protest posters, including the beautiful ones above by Shepard Fairey. You may recognize his style because he drew the iconic Barack Obama poster. Shepard Fairey and his fellow artists Jessica Sabogai and Ernesta Yerena have raised over a million dollars on their Kickstarter campaign for a public art project called We The People. They will disrupt the inauguration with a flood of art. I don’t know how it’s all going to come down, but I’m looking forward to finding out.