This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

I’m filing this dispatch from Minnesota, where I’ve arrived early for a mystery convention. The last two Bouchercon gatherings of 2020 and 2021 were virtual, making this year’s gathering in Minneapolis especially tempting to me, not only to see mystery friends but to revisit the beautiful “City of Lakes” that was my home during 2006-2012; most of my childhood was spent in nearby St. Paul, Minneapolis’s so-called twin city, which also has lakes throughout the suburban parts of the city.

Driving made sense because I could spend the weekend prior to the mystery gathering in Bayfield, a historic hamlet on Lake Superior in Northern Wisconsin. Because I was driving an 18-hour trip, the journey to Bayfield was preceded by a night in Madison, which had gorgeous Lake Monona right out my hotel window. Without a conscious plan, I’d floated into a miniature holiday of northern waters, or lands of lakes.

Wisconsin has a town named Land O’Lakes, and in the 1920s, a group of Minnesota dairy farmers banded together to market their products around the country—naming themselves Land O’Lakes. The accent between Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan is nearly identical, and they all share Superior. The state college systems in Minnesota and Wisconsin have a reciprocal agreement for instate tuition rates, allowing students a chance to stretch beyond their immediate homes without spending extra.

Lake Superior is the world’s largest freshwater lake, if judged by surface area. That makes it too large for the casual exerciser, as it would involve passing through Wisconsin, Minnesota, Indiana, and Canada! I’d been near this lake before at one of its Minnesota shore cities—Duluth. This time, I gazed at it from the very scenic viewpoint of Bayfield, a Victorian town that was built in the 1870s by developers who built grandly because they believed it might become Lake Superior’s own Chicago. Bayfield had some fish canning and lumber industries, but it never became a metropolis—a boon for visitors looking for unspoiled views and delightful ferry rides to the nearby Apostle Islands, including Madeline Island, a 20-minute ferry ride away.

Recently communities are recognizing and acknowledging that lakes were homes to indigenous communities who were driven away by settlers, missionaries, and the U.S. government soldiers. Gichigami, meaning Big Water in Ojibwe, is the first name for Superior. French missionaries in the 1600s called it “Superiore” based on its geographic position, and the name has remained. Monona, one of four lakes near Madison, takes its name from Chippewa language and is said to mean “beautiful”; although the naming was done by an American developer. The original name in Chippewa language was Tcheehobekeelakaytela, meaning “Tepee Lake.”

Minneapolis is another example of an Anglicization of Native language. Minne is a Sioux word meaning “water,” and the area of Southern Minnesota was developed by Whites only after US soldiers violently drove off the Dakota and Chippewa living in the area, resettling them in reservations in distant, inhospitable territory.

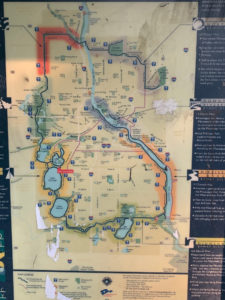

Minneapolis contains a chain of lakes, with some of them original to the land and others man-made. Lake of the Isles, one block from my Airbnb, was created in the 1880s by dredging a small existing lake with four islands inside (Wita Topa means four islands in the Dakota language). The lake was joined to a nearby marsh, and later connected to two other nearby lakes, one named Cedar, and the other named Lake Calhoun. The city’s most extravagant mansions were built around Lake of the Isles, most of them standing.

In the early 2000’s, a controversy arose around Lake Calhoun. The lake was named in the 1800s in honor of John C. Calhoun, the former Secretary of War who’d surveyed the land for Fort Snelling, and who was also a well-known slave owner and politician advocating for slavery. A Native-led group requested the Park Board change the name, and in 2017, the board voted unanimously in favor of changing signage for the lake to include the original Dakota name. Legal contests followed from a group who argued that the Park Board the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources didn’t have the right to change the name. The name change was refuted by the Minnesota legislature, but the battle went to the Minnesota Supreme Court, which in 2020 upheld the right of the Department of Natural Resources to call the lake Bde Maka Ska (pronounced Be-DAY Mah-KAH-Ska). I remember when my Twin Cities friends started using the new name when we chatted on the phone. They could say it so easily, and I stumbled. But now, I’m used to it and like it much better.

As I revisit such beautiful lakes on my journey, I feel surrounded by so much that is weighty. Walking with my husband around Lake of the Isles this morning, my mind turned to my two voluntary moves away from Minnesota to Maryland. The first time I was eighteen and desperate to go to college among a more diverse community. The second time I moved I was forty-eight and struggling with the feeling that I would never feel like I belonged in the Midwest, despite my love of family and the environment.The irony is that I’ve visited here three times in 2022. And each time I return, I doubt my move; all the while realizing how lucky I am to have a choice about such matters, unlike the first people who loved these lakes.