This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

It had been a challenging week. The shooting of two Indian professionals in a Kansas bar was followed by the knifing of an Indian-American outside his home and the news that a number of South Asian business owners have had their shops torched. Whether or not the attackers misjudged these South Asians as “Arabic” or “Muslim” doesn’t matter. It only means that the danger to immigrants has become very personal for me.

I felt the need for a temporary retreat from bad news, so I went looking for a Bollywood movie.

Fortunately, it’s easy to find Indian movies in my state. These days, if you want to catch a film in Hindi, Tamil, Kannada or Bengali, it’s likely that a megaplex in the AMC or Regal chain is screening it—often late at night, or just a few times a week. A great way to hunt for Indian movies is through Pragathi.com.

You may have heard that Indian movies take some time to watch. They are typically three hours long with a 20-minute intermission (observed in India, but skipped in the US and Canada). On a Tuesday afternoon in Arundel Mills, Maryland, I paid a whopping $5.64 to be the sole viewer for the afternoon matinee of Rangoon.

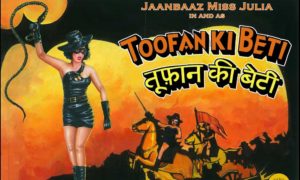

Rangoon hit India’s screens in late February and made it here within the same week. The title is rather misleading, because nothing happens in the former capital city of Burma, now Myanmar. Yes, there are plenty of nature scenes in the jungle along the Irrawaddy River between Burma and India. I suspect the vague name was give to draw male viewership, because the film’s central focus is a fictional 1940s film star called “Miss Julia” played by Kangana Ranaut.

Julia is a beautiful Anglo-Indian actress best known for the line “Bloody Hell!” though her songs and dialogue are all in Hindi. As the top stuntwoman actress in Bollywood, she’s in love with Rusi Billimoria, a former film star who lost his right hand performing a film stunt. Rusi and his father are wealthy Parsis (Indian Zoroastrians) who own the cinema company; Rusi directs while his father sits in Bombay and tells him what to do. Their studio is pro-British, so when an army general tells Rusi he’d like Miss Julia to come to the Burma front to perform for the soldiers, Rusi’s father says she must go. Julia is horrified by the idea of going into the jungle, but she’s packed on a train with a handsome bodyguard from the army who attempts to prevent her escape.

True to the romantic-adventure genre, there are plenty of song and dance scenes, made even better because of the historical references in some numbers to Hitler and Churchill. The visions of late colonial homes and film studios are gorgeous, not to mention the river and jungle. Kangana Ranaut in the star role is beautiful and haughty, and a kick-ass pilot, motorcyclist, horseback rider, dart thrower, and dancer. A dance scene on top of a train is film convention—however, Miss Julia’s fights atop a vintage Northwest Frontier Train reprised and beat actor Shah Rukh Khan’s famous “Chaiyya Chaiyya” dance scene from the late 1990s. Her songs, sung by Bollywood legend Farah Khan, are great.

And now for a brief intermission into some facts:

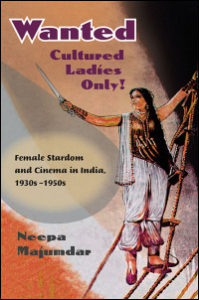

Miss Julia, the actress character, has historic origins. Soon after silent pictures began, a subgenre developed wherein actresses played physically daring roles, often fighting men with their fists, knives, swords, and guns. In Bollywood, these actresses were typically Anglo-Indian, Jewish or American rather than 100% Indian. Film producers feared offending India’s religious communities by subjecting Hindu, Muslim or Parsi women to the male gaze. These outsider actresses typically had Hindu names and played Indians. And at a time when the British were in control—and Indian men couldn’t act out—sword-wielding women were a very subtle way of expressing nationalism. You can read more about the history of Indian women actresses in Wanted: Cultured Ladies Only! by Neepa Majumdar.

From Majumdar’s excellent book, I learned that one of the first action stars of Indian cinema was Sulochana, originally named Ruby Myers, who began in silent films and transitioned to talkies. Sulochana who was considered both a beauty and a flapper, acted in five to six films a year during her heyday. Many of her roles involved the idea of giving up a debauched Western existence for a more simple and honorable Indian identity.

Sulochana’s best-known film was Cinema Queen (1925) which is about the travails of a movie actress—just like Rangoon.

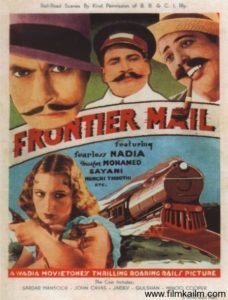

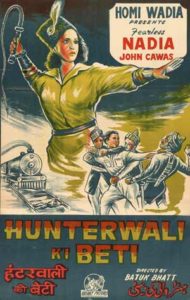

Some articles in the Indian press compare “Miss Julia” character in Rangoon with the famous 1930s stunt actress known as Fearless Nadia. The woman who was born in Australia and had Scottish-Australian-Greek ethnicity came to India when her father was a soldier in the Indian Army. After his death, she was first a circus performer and later an actress in over 50 movies produced by Wadia Tone pictures run by two Parsi brothers. Her most famous film, Hunterwali, tells the story of a princess who dons a mask and cracks a whip when she goes forward to avenge injustice.

Descendants of the Wadia brothers are concerned the film may have breeched the trademarks they hold on the character of Fearless Nadia. But in addition to Sulochana, there were other Indian women stars in the genre with names like Miss Zebunissa and Miss Padma. And Fearless Nadia was a blonde who never disguised her European origins. In Rangoon, Miss Julia bluntly explains to a snobbish maharani that she was born to an unmarried Indian mother.

Okay, the intermission on Indian film history is over and we are back to Rangoon—the modern remake of a 1940’s woman-centric action picture.

Every good Indian film must have a villain, and the British general takes on that role with such awful lines as “Because I’m white I’m right.” There’s also a love triangle; Julia goes missing and is rescued by handsome Sergeant Nawab Malik, her mysterious bodyguard. Nobody will be surprised by the love triangle that develops between these two and Rusi; but the grand finale, where the battle for loyalty and India’s future plays out on a rope bridge, is simply breathtaking. For a look at some videos of dance scenes, check out this Times of India review.

The story’s underlying theme is the battle between the Indian Army (British-government controlled) and the Indian National Army (INA) sponsored by the Japanese. These forces really did fight along the Burma-India border during the late years of the war. In this film, there’s a secret mission to deliver a jewel-encrusted Indian prince’s sword to ensure this army of rebels would have funds they needed to support an invasion without needing the Japanese. I wrote about the INA in my books The Sleeping Dictionary and India Gray, so it was exciting to see a partially accurate depiction of the forgotten army.

I walked into Rangoon feeling like a person at risk, but left singing Jana Gana Mana, the Tagore poem that later became the anthem of independent India. Miss Julia and her comrades had stood up to those who wanted to keep them in their place. Onward I’ll go.