I’m making cookies today with a 15-year-old daughter who likes the baking, and a 12-year-old son who always seems to know when they’re ready to come out of the oven. Deciding whether to go chocolate or coconut is a sweet moment that breaks up our non-Hallmark Card life. Peace comes when we are repeating activities that have continued from early childhood.

Inevitably, winter brings memories, and not all of them are of footsteps in the snow. During the first winter that I spent with my daughter, she was just 7 months old. I’d adopted her from an orphanage in Kerala, and we were staying in Kolkata, waiting for the INS to send permission for her to enter to the United States with me. There were tremendous bureaucratic complications. It was a stressful time, even though I was staying with kind and supportive relatives.

Inevitably, winter brings memories, and not all of them are of footsteps in the snow. During the first winter that I spent with my daughter, she was just 7 months old. I’d adopted her from an orphanage in Kerala, and we were staying in Kolkata, waiting for the INS to send permission for her to enter to the United States with me. There were tremendous bureaucratic complications. It was a stressful time, even though I was staying with kind and supportive relatives.

Something that was supposed to make life simpler for me was the presence of an ayah, or nanny. I didn’t ask to have someone come in and take over my role 12 hours a day. But the two manservants who already worked in my grandparents’ apartment were males busy with a number of chores. They would not be able to carry out their normal work if a baby was not professionally tended by someone else. All my protestations of wanting to do it myself were overruled.

So the day after my sister and I arrived and set up in the guest bedroom with Baby Pia, an ayah agency in the neighborhood sent over a small, slim young woman with sparkling eyes and a sweet smile. Her name was Bharoti. She was eager to learn a few words of English and teach us Bengali. She was about eighteen, I think, and married to a taxi driver. Her own baby was living two hundred miles from her in the mountain village where she came from, cared for by her own mother, in order that Bharoti and her husband could make money in the city.

I tried to approach the situation positively, because I felt badly that Bharoti could not be with her own child. I reasoned that Bharoti could be more of a language tutor to my sister and me, and I could still be the real mother. I needed to send daily faxes to my husband regarding our immigration nightmare, which meant leaving the apartment. But for every hour I left my baby with her ayah, anxiety coursed through me. Bharoti was affectionate and attentive, but my aunt caught Bharoti giving Pia formula that had been mailed with unboiled water, and I saw the ayah chatting up street people while holding Pia, which made me worried she might give away information about where we lived. One afternoon when I was home, Bharoti opened the door and a rough-looking threesome stormed inside, refusing to leave until I’d paid them off (hijra, or transgender entertainers, make their living through extortion of people in the middle of happy life events like new babies and weddings).

But the most frightening thing for me was the ease with which Pia accepted this change in care and nestled peacefully in her ayah’s arms. When we went out shopping at Bengal Home Industries one day, Bharoti insisted on holding Pia, and foreign shoppers smiled at the two of them, looking like mother and child.

My tone with Bharoti became cool, and I began watching her like a hawk. I felt guilty about it, like I was turning into a British colonial memsaheb. Very quickly, I spiraled into the belief that I was a useless mother and my baby couldn’t attach to me.

After another month, we received government approval to return to the United States. I cried when I said goodbye to Bharoti and gave her a big tip. She had new work starting the next day. During my next trip to Kolkata, when Pia was nine, I tried to find Bharoti through the agency; but there was no record of her whereabouts. I’ve always hoped that she became able to return to her own daughter in the hills.

Years later, when I was researching my historical novel, THE SLEEPING DICTIONARY, I read many accounts of British children who felt very close to their ayahs and lived out their childhoods completely separate from their parents. Remembering how hard the ayah relationship was for me, I longed to write about this world of mothers, children and ayahs in the book…but there was no room in a book that was already more than 500 pages.

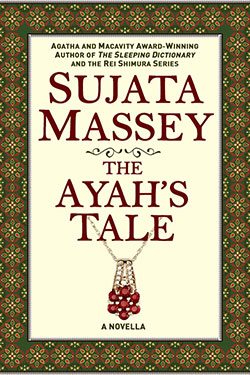

Out of this idea, I’ve created a 40,000 word novella called THE AYAH’S TALE, which examines the life in a 1920s British-Bengali colonial household from both a child’s point of view and the ayah’s. Menakshi is a 16-year-old girl Indian Christian girl whose middle-class household has fallen on hard times–which means she must leave high school to work as an ayah. Julian is a bright, neglected six-year-old boy who drinks up her attention and begins to see India around him differently, because of her. Marjorie Millings is his mother: a sad, disconnected woman who looks for love outside of their elegant bungalow. Ram Hollander is a young Anglo-Indian who works on the railways. It’s on the Bengal-Nagpur Railways that the characters collide and begin a journey toward change.

Out of this idea, I’ve created a 40,000 word novella called THE AYAH’S TALE, which examines the life in a 1920s British-Bengali colonial household from both a child’s point of view and the ayah’s. Menakshi is a 16-year-old girl Indian Christian girl whose middle-class household has fallen on hard times–which means she must leave high school to work as an ayah. Julian is a bright, neglected six-year-old boy who drinks up her attention and begins to see India around him differently, because of her. Marjorie Millings is his mother: a sad, disconnected woman who looks for love outside of their elegant bungalow. Ram Hollander is a young Anglo-Indian who works on the railways. It’s on the Bengal-Nagpur Railways that the characters collide and begin a journey toward change.

You can find THE AYAH’S TALE as an Ebook at Amazon. If you would like to receive a free short story and receive more email updates on India, Japan and writing, click here to subscribe to my mailing list.

Happy Winter reading.

Sujata

Hi there would you mind sharing which blog platform

you’re working with? I’m planning to start my own blog soon but I’m having a tough time deciding between BlogEngine/Wordpress/B2evolution and Drupal.

The reason I ask is because your design seems different then most blogs and

I’m looking for something unique. P.S Sorry for

getting off-topic but I had to ask!

Hi Kina, I’m using wordpress.com and it’s pretty easy, though my web designer set it up and taught me everything!

Hi Sujata,

Will this be on sale in the iTunes Store?

Sincerely,

Anitra 🙂

Hi Anitra, I have not contracted with anyone to produce The Ayah’s Tale as an audiobook…but I hope that it happens.

Sujata

Great to “find” you again. Got to try to get hold of your new books. Probably they won’t be translated to Finnish in the near future. Your Pia has grown so much. My son moved away from home last July at the age of 18. Oh that was hard, though he lives only 2 km away. (was reading J Lahiris the Lowland and somehow you came to my mind…. It’s been long time since the Reis…) Take care

Wow, what an interesting post.

The role of the ayah brings to mind the “relationship” between black “nannies” in the south and their white charges.

I wish you could have found Bharoti, to see how her life has fared.

I’m curious to hear what happened with the hijra! Sounds quite troubling.

It was a pleasure to hear you speak at the Govans Library. It was fun and informative.

I wish you much success with the Sleeping Dictionary!

Dear Ms. Massey:

Ever since discovering your first book (salaryman’s wife,

I think?) during a stay in Japan, I have been following Rei’s adventures with great pleasure. I suppose my background of Indian origin, living in Hawaii for long and spending extended stays in Japan and many friends and exposure to Japan made for perhaps a special appreciation of those books. Especially enjoyed her recent Hawaiian adventure.

Your new series with British colonial background in India looks promising, but maybe not easy.

Congratulations, thank you for the pleasure and hope to see Rei again in near future.

Best regards

Sandip

Hi Sandip, please call me Sujata. it sounds like you have gone to a lot of the same places as me! So far there’s one Indian historical suspense novel out:in the US it’s The Sleeping Dictionary and in India it’s called The City of Palaces and I’m happy that Rei fans are enjoying it. There will be a Rei book out late fall called The Kizuna Coast; you’ll find it most easily at online retailers. Thanks for your kind congratulations.

Thanks, Sujata. Sorry about the initial formal greeting.

I read the Ayah’s tale and started the a Sleeping dictionary.

So very different from the Rei books.

Shows versatility!

Sandip