This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

At birth, we are given a name that’s not our choice, but that of our parents or guardians. It also can happen on a macro-level when you think of the names of countries. And when we understand how people outside the home react to our name—our self-image develops.

The Prime Minister of India and members of his ruling political party, the Bharatiya Janata Party, have recently begun referring to India as Bharat. Hindu Nationalists believe Bharat is the Sanskrit-based name for the subcontinent and that using it officially removes the imprint of colonizer’s language, much as changing city names has done. Yet Bharat is a word that comes out of Hindu history, and not everyone in India is a Hindu. Such a name change, if it’s more than temporary, will have a bearing on how citizens feel about their homeland.

I grew up with an Indian name that can be pronounced correctly if you follow the English sounds of the letters: Sue-JAH-tah. Still, my six-letter name was confounding to many people as I grew up. During my school years in suburban Minnesota, teachers would stop dead when my name showed up on the classroom roll. Snickers from kids followed as the teacher mispronounced my name, or just looked toward me—usually the only brown kid in the room—and said “I can’t pronounce this.” Kids twisted my name into their own grotesque teasing adaptations. Adults often said, “Can I just call you Sue? or even “I’m going to call you Sue.”

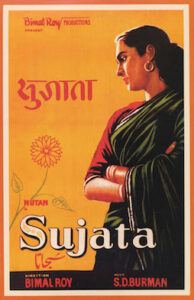

Indians often ask me whether my father chose my name because of a famous 1959 Bimal Roy movie called Sujata. Starring the actress Nutan, the film tells a love story that almost tanks because of caste discrimination. My father did see the film, but that wasn’t how the name came into his heart. Instead, the Sujata he knew was an older, very bright student at his high school who became a close friend to him and another boy, offering them advice on their academic pursuits and life. Sujata and my father corresponded by letter during their early years at separate colleges. One day, Sujata wrote to say that she was engaged. Out of propriety, my father never wrote to her again. Yet his sentimentality led him to suggest the name to my German mother. She agreed—slipping in one of her family’s traditionally passed-down names, Christine, for my middle name. Both of my younger sisters have one Eastern name and one Western name; sometimes the order is mixed up, but both names are there, proudly bicultural.

When I reached Baltimore for college, I didn’t have the same kind of trouble with people balking at my name. The undergraduate mix at Johns Hopkins was highly international with lots of classmates having names that reflected their unique heritage, or their parents’ imaginations. I began relaxing into my own name and didn’t feel like it was a burden. But as I left academe to become a reporter in a ‘real world’ city, it seemed many people I rang up for interviews could master either my first or last name—but not both. And this made me feel different again.

I married in the early 1990s, an era in which about half of professional women retained their maiden names, and the rest either hyphenated or assumed the husband’s surname. I chose to say goodbye to Banerjee and adopted Massey. My husband didn’t ask me to do it, but I was thinking ahead to the future… my byline on a book jacket! I felt that having a name that couldn’t be pigeon-holed to one country gave me more psychic freedom to write about a lot of places.

I did write about many places. But ironically, I discovered that to many in India, Massey is an Indian name—and Indians care a lot about what names mean. I’ve had many situations wherein Indians have asked if I’m a Punjabi or married to an Indian Christian, or Anglo-Indian. There are journalists who even explored this issue in print.

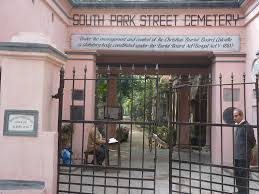

“Masseys are buried here! They are in town! Who are your relatives?” the Anglo-Indian caretaker of the South Park Street Cemetery in Kolkata asked with great excitement when I visited. He refused to believe I could not be related—and perhaps a few of my husband’s British ancestors did sail for India.

The space where I have the most fun thinking about names is while writing fiction. My first series was set in Japan. Just like India, Japanese names translated to English are spelled phonetically. Names like Ito and Taro and Shimura didn’t cause too many stumbles. My female protagonist is named Rei. Its pronunciation, “like a ray of light” was explained in the book by the character. And of course a sleuth shines light on crime! The name Rei has multiple meanings in Japan depending on which kanji character is used to express it. The meaning I chose for my character Rei was crystal clarity, which also is synonymous with her role.

For my books set in India, I found myself suddenly writing huge casts of characters, all of whom demanded unique names. I also wanted readers new to these names to be able to keep track of them in their mind. I turned to a book that I’d originally bought to name my own future children. It is titled Pick a Pretty Indian Name for Your Baby. The book’s authors, Meenal Atul Pandya and Rashmee Pandya-Bhanot, present names that they think are less likely to be mispronounced or translate poorly, with examples given in the introduction like Viral and Naval (I have used Naval in fiction without incident!). Another aspect I like about this book is the meaning listed next to each name. Thus, I selected the name Oshadhi, which means medicine, for a character who’s an unofficial family pharmacist.

I also find character names as I encounter them in real life. I met a lovely lady called Sunanda (the name means ‘beauty’) who was the head of housekeeping at the Royal Bombay Yacht Club. Every time we passed each other in the building, Sunanda greeted me with confidence, and I saw what pride and responsibility she took in her work. I gave her name to a young woman character with incredible courage and heart.

The Parsi people are followers of the Zoroastrian religion who emigrated to India up to a thousand years ago. Parsis typically have Persian or Western first names, and last names that relate to a place or occupation. These surnames can be gloriously specific, like Sodabottlewalla or Engineer or Banker. Quite a few Parsi names start with the letters Z or X, memorable letters that tempt me toward literary use. However, the historian Dinyar Patel pointed out that very few Z names existed before the mid-twentieth century. Sighing to myself, I held back on the Zs, although I am happy to have a male character called Xerxes.

The heroine of my series is Perveen Mistry, a young Parsi woman whose surname means construction, the line of business her ancestors started with. The name Perveen is means ‘star’ which I think is excellent for someone who features in book after book. Amongst Parsis, Pervin and Parveen are alternate spellings.

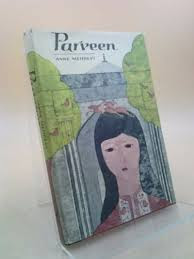

I was looking for a good heroine’s name back in 2015 when I was working on a book proposal. I had no idea what I would choose, so I went online looking at lists of Parsi female names. When I saw Perveen, a happy memory came back to me. Around the age of ten, I’d devoured a wonderful historical juvenile novel titled Parveen by Anne Sinclair Mehdevi. The novel was about a 16-year-old Persian-American who has a life-changing adventure visiting her divorced father in Persia. The novel takes place in 1921, an eerie symmetry with my own series, which I chose to start in 1921 Bombay.

Recently, I searched used book websites to find an image of the 1969 book Parveen. Very few copies still exist, and I’m ecstatic that one of them is on its way toward my home, at quite a reasonable price. After Parveen arrives, I can nestle her next to my own Perveen: books written more than fifty years apart yet linked in my literary imagination.

I love this blog post! It’s so interesting to read about different cultures and their naming customs. I’m from India and my family name is Massey. I’ve always been curious about how it came about and I’m glad to