This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

I grew up in a gray house in Minnesota that didn’t get much light. Yet because my mother lined all the windows with plants, it never felt dark. Everywhere, there would be an African violet, or a frilly fern, or leggy begonias. In May, one family chore was shifting the dozens of houseplants out to the screened porch. This was ultimately good news, because I didn’t have to worry if I spilled water onto the flagstone floor. I loved the plants, but I was aware of how many things could go wrong if you overwatered or got an insect infestation.

I thought I was too busy to keep plants when I set up my first apartment after college in Baltimore. My only plant involvement was with the cut branches and blooms used in ikebana, the minimalist Japanese art of flower arranging, and that hobby came about because I lived for some time in Japan. After my husband Tony and I returned to Baltimore, I learned in bits and pieces from kindly neighbors about gardening outdoors; first from an elderly Englishwoman who oversaw volunteer gardeners at The Ambassador, our grand 1920s apartment building, and then at our succeeding houses, all of which were handed over to us by previous residents who had developed their gardens. My hands were getting dirtier; but gardening was limited to spring and summer only.

In the summer of 2021, I received a gift from my friend, the mystery novelist Susan Elia MacNeal. Susan had placed an order with a Baltimore business named The Modest Florist. The Modest Florist delivered a ceramic bowl planted with three different green plants that I now understand are chamaedorea (parlor palm), dracaena (lucky bamboo) and philodendron. The green trio survived, no matter how much or little I tended to them. And with this experience, a tiny blade of curiosity grew. I didn’t mind watering a dish garden weekly. Caring for an indoor plant felt a lot like my writing process; tending something small, fussing inordinately, and watching it develop.

I dared to set up some potted plants on the porch, where I wouldn’t have fear of watering mishaps. I was thrilled to find classical looking tall planters that looked like ceramic, but that were actually a lightweight fabricated material that I could move with my own two hands. I filled two of these white urns with potting soil and bird of paradise, which shot up happily. Soon, my porch was a hodge-podge nursery, including geraniums from friends, palms from a big box store, and a key lime bush that I mail ordered from a Florida nursery. A green-thumb couple who were moving out of state sold their precious ficus, as well as a few other prize plants—a decision they made on the basis of my porches.

One day, I heard about a sale of the uber-trendy fiddle-leaf fig. I got the last one left at Aldi. Although one of the fiddle leaves will always be half-brown, I have concluded that the plant is doing fine. This is the way it is; and the brown is proof that my plants are the real thing.

As fall arrived, my plants remained valiantly alive on my porch I finally brought them inside during October, after a few freezing nights. As I looked around for winter residency spots, I realized with surprise that my 1897 cottage had plenty of room for plants—space I had never really seen for it was. A sunroom where I do most of my writing had two walls of windows, and an ancient side porch, now closed in and working as a butler’s pantry, had excellent southern and western windows.

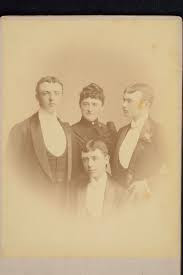

I was excited to learn about an exhibition, History of Houseplants, at Evergreen House, an Italianate 1850s mansion near me. The grand residence, now part of Johns Hopkins Museums, was owned first by T. Harrison Garrett, president of B&O Railroad, and later by his eldest son, John Work Garrett, a diplomat who divided his time between Evergreen and his overseas postings, where he and his wife collected art and antiques that augmented his wealthy parents’ collections. Evergreen House is open to the public, and when I visited Evergreen House over the last weekend, I took a deep dive into houseplant stylings of the Victorians through the Edwardians and Deco periods.

One fascinating aspect was learning about the origins of gardening as a ladies’ hobby. Women’s clubs tried to promote plant growing throughout society as a wholesome pastime. In 1911, a group of Baltimore women started a festival called Flower Mart, with plant stands and entertainment set up around the city’s Washington Monument that was intended to inspire the whole city.

During the Victorian era and the early twentieth century, the formerly natural countryside around Evergreen House was being absorbed into a city of row-houses. Cities like London, New York and Baltimore were becoming black with coal smoke, and agrarian workers’ children were coming to these places to work in industry and at service jobs. Plants were a psychological respite; a reaching out to the fading, faraway landscape. Some plants, like ferns, were believed to reproduce through spores rather than cross-plant fertilization, making their propagation an ideally chaste pursuit for young women. In Britain from 1830 up through World War II, fern fever took such a great hold with the public that the Victorian writer Charles Kingsley chose to satirize it as “pteridomania.”

Kingsley wrote: “Your daughters, perhaps, have been seized with the prevailing pteridomania, and are collecting and buying ferns…yet you cannot deny that they find enjoyment in it, are more active, more cheerful, more self-forgetful over it, than they would have been over novels and gossip, crochet and Berlin-wool.”

Alice Whitridge Garrett, the house’s first doyenne, oversaw a fern house that took a staff of fifty to operate.

In the 1920s, her daughter-in-law, Alice Warder Garrett, who married the eldest son, John Work Garrett, decided to tear down the fern house as a cost-saving measure.

After strolling through Evergreen House, my imagination was stirred to the point I was becoming ‘self-forgetful.’ I whiled away an hour on the Internet, reading articles describing Victorian plant culture, which partly arose due to a reaction against urbanization, as well as tall window designs modern, piped house heating. I thought about the style of my own 1897 house, which has over 50 windows. Too many windows to find a window cleaner, I’ve always thought.

The windows were waiting for plants, I realized. I also recalled the still-empty rusty iron plant stand that I’d impulsively bought at an antiques store in Hampden a few weeks ago. This Victorian stand has been waiting for something to bring it back to life.

I conferred with a plantsman who looked at the simple stand, which is about three feet high, and agreed with me that it would best suit nephrolepsis exaltata, which sounds entirely sinister until you realize it’s just the proper name for a Boston Fern. And the odd city name supposedly was born because of one rogue plant discovered in a shipment of ferns from Philadelphia to Boston.

Gazing out of my smudged Victorian windows into my winter garden, I note the barren brown earth where I will be on my knees in a few months. Most the new bed will probably be filled with shade tolerant native ferns. Garden work lies ahead with its joys and pains. For now, I’m happy to play at cultivation inside four walls.