This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

When life is stressful, resting my eyes on clear surfaces and straight lines helps me take a deep breath. Getting through the last pages of an edit is always a tough time—I’m housebound and frustrated. So during one of my stomps around the house, I caught sight of some overcrowded bookshelves and became obsessed with purging them. I expected this book cleanse would be easier work than my semi-annual clean-outs of the towering shelves in our dining room. This was a simple matter of tending to the walnut and maple-joined bookcases my husband built in our butler’s pantry twelve years ago. He’s tremendously creative, and it its a sturdy, six-foot long, granite-topped set of two sturdy shelves that can hold almost two hundred cookbooks.

I find it difficult to retire a cookbook. This is no matter whether it’s been used a lot in the past and has become threadbare or is pristine because of minimal use. I probably struggle also because I have strong feelings about cookbook authors. These writers often have professional cooking backgrounds. They test their recipes multiple times, they use science and history, and they are usually involved in the food styling and photography. My very favorite cookbook writers are also charming storytellers who mix personal tales along with teaspoons. This contingent is headed by the dearly departed M.F.K. Fisher, Laurie Colwin and Elizabeth David. Still living, and writing wonderful stories along with their recipes, are Molly Wizenberg, Amanda Hesser, Dorie Greenspan, Hannah Che, and Priya Krishna.

Until now, I hadn’t realized that so many food writing favorites are women. Is focusing on writing because of women’s exclusion from chef jobs for so many years? Or is it because cookbooks are a subgenre of “women’s books?” What about the madness of dessert cookbook reading—does reading them hit the same brain receptors as a kiss?

There still are male authors on the shelves, of course. The most favored one is the late Craig Claiborne, who was restaurant critic and food editor at The New York Times from 1957 to 1986. Claiborne doesn’t make time for stories, but he writes luscious recipes, never mind the vast amounts of butter and cream in most of them. Claiborne is known for multiple books, but our family favorite was The New York Times International Cookbook, published in 1971, the time my parents were setting up house in Minnesota. I can still picture the thick, dog-eared hardcover taking up a big part of a small shelf in the tiny hall just off the kitchen. Whenever my parents wanted to make something exotic like Greek pastitsio or Hungarian goulash, they cooked from this book. The three children in our family had the chore of cooking supper once a week; the good news was it could be anything we wished. I tended to use the cookbook’s French section, because I was enthralled with the poetic names of the soups and entrees. My sisters favored the Italian section and became adept with spaghetti and meatballs, spaghetti carbonara, and even pizza. Yes—in the 1970s, in our family, nobody ever phoned out for pizza delivery—it was made from scratch! My parents and I sometimes had a conversation about what we would cook for Mr. Claiborne if he ever came to dinner. I wanted to make Chicken Chasseur, but my parents said Indian. They were firm in their belief that this was one area of cooking in which they were accomplished, and he was an amateur.

After I went away to college in Baltimore, I was thrilled to find a first edition of The New York Times International Cookbook in a used bookshop. I used it to cook for roommates and friends. The first meal I ever cooked for my future husband, during our college days, was his French section’s Chicken with Cream and Tomatoes. I was nervous about Tony having to wait too long, so I cooked very fast—and part of the interior of the chicken breasts was a vivid pink.

The following summer, I had a New York romance and was exposed to sophisticated cooking of the moment. I became enchanted with a cookbook that may have defined the 1980s: The Silver Palate Cookbook, written by Julee Rosso and Sheila Lukins. I learned about the luscious recipes paging through the book while visiting my boyfriend’s mother’s dream kitchen—and yes, she cooked from it—and did it well. My romance fizzled, but the fabulous mother generously gave me my own copy of the cookbook. I left New York without a boyfriend, but I now had a mastery of pesto and dark chocolate cake.

After college I went to the Baltimore Evening Sun as a general assignment features reporter, and cookbooks fell into my life at a rapid pace. It all started because I offered my reviewing services to a food editor overwhelmed by dozens of books sent by publishers each week. I tried out at least one recipe from each book and wrote reviews, getting letters of thanks—and sometimes anger—from the book’s authors. In the process I filled my IKEA Billy bookcases with that spanned such topics Thanksgiving dishes, biscuits and scones, and Indian microwave cooking.

I gave away about a third of my cookbook collection before I got married and moved to Japan. At the Japanese bookstore Kinokuniya, I bought several beautifully photographed Japanese cookbooks—not quite admitting to myself that the dishes were more time-consuming than I could manage. But I still ate through those books with my eyes.

It’s the same for me now that I’m back in the United States: I have an insatiable hunger for cookbooks that is only amplified by cookbook author interviews on podcasts and cooking videos on YouTube and Instagram. Because of the plethora of food bloggers, it’s easy to find recipes for free on the internet; however, the likelihood of these recipes failing is far greater than recipes by an experienced food writer tested and cleared for publication in a book. Because of the rise of googling for recipes, I fear for the economic wellbeing of cookbook writers, and this is another reason why I rationalize my cookbook buying.

Passing the milestone of forty, health became a powerful reason to invest in new cookbooks. I find myself going through phases of various eating styles with great enthusiasm. My vegetarian period involved several books on Indian vegetarianism by Madhur Jaffrey, and American books like Mark Bittman’s 996-page doorstopper, How To Cook Everything Vegetarian. Mark Bittman also helped me through a pescatarian phase with his seminal book, Fish. During the years my kids were young, food sensitivities flew by the wayside. In the interest of time management, I turned to slow cooker books and anything that had the word “Quick” on the cover.

Late at night is still my quiet time and the perfect opportunity to turn to rereading my favorite food memoirs. My love for literary food writing began when I accidentally discovered a few M.F.K. Fisher classics that described her years living and dining in France—from glorious carefree days to severe food shortages during World War II. I devoured it all. The example of brilliant M.F.K. Fisher led me to think I could make the best of leaving the newspaper to be a trailing spouse—if it were overseas. As a newlywed—just like M.F.K.!—I would settle abroad in an unfamiliar, stimulating location where I would gamely take up a life of eating at restaurants, shopping at exotic markets, and learning to cook another cuisine.

And reading these books brings me back to that honeymoon period with Tony in Japan. Throughout our time living in Hayama, a small town an hour south of Tokyo, we explored every type of café and home dining experience. This translated to rotary sushi bars, tea ceremonies, tofu-making classes, and old-fashioned US Navy dinners where a Campbell’s Soup-based casserole might be served with fanfare. But instead of writing a food memoir about this period, I found myself drawn writing a mystery that included food. For instance, there’s a horse sashimi appetizer in The Salaryman’s Wife that is taken straight from my memory of a tense New Year’s Eve dinner in the Japanese Alps. Another book, The Pearl Diver, delves into the backstage world of a Japanese fusion restaurant. Years later, I can’t imagine writing a book without the help of restaurant experiences or cookbooks. I often turn to regional Indian cookbooks to set the tables in scenes within the Perveen Mistry series. The Widows of Malabar Hill’s paperback edition contains an easy menu of dinner recipes meant for book-club potluck meals.

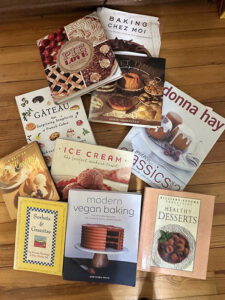

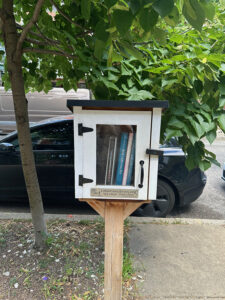

So now that I’ve kissed a few cookbooks goodbye, I have good news. My brain calmed, and I finished my book edit. And I predict the eleven books I’ve left at various Little Free Libraries around the city will soon find themselves in new homes, inspiring people—whether they make a meal or not.

I may have to send you a Texas BBQ cookbook – as I too am a lover of cookbooks. Love all of your books – I hope Gulnaz comes home – I would also want Colin to continue in Perveen’s life. Didn’t Perveen’s first husband die in the last book? All fascinating characters – thank you!