This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

Surely, every writer has a different equation of how much writing they leave as is—and how much they willingly alter. Fine tuning is a major part of my work these days, and it’s every bit as challenging for me as getting the first draft on paper. For my upcoming book, two editors read my manuscript and inserted line by line queries. After they finished, a copy editor and a proofreader got to it. A lot of focused, analytical minds catch inconsistencies and errors, and I’m grateful.

Before one of my novels goes into print, I rewrite it three or four times. I dwell the most on the line-edit draft. A line-edit happens after a book has been edited by a content editor with suggestions for theme and consistency and suggested changes in direction. Now the same editor—or an assisting editor—goes word by word, flagging repeated words, inconsistencies, and the like. When I submit a 425-page manuscript, and each page averages at last three editing marks, that means there are more than 1200 points for me to deliberate over (or should it be, “over which to deliberate”?) In Microsoft Word, color changes in the text highlight anything that has been rewritten by an editor. Any comments appear in thought balloons on the margin.

All kinds of things that looked smashing and tight when I sent off that draft to be line-edited appear rambling and poorly worded to me on close reflection. And then, when I rewrite one sentence, it usually leads to a string of changes due to new ways of thinking; changes that my editors didn’t expect and now need to edit again! And I create more work for myself because upon this third-or-so reading, I start to wonder if I got the research right.

Here’s an example of how I might go into overdrive on an edit. Let’s look at what I’d call the “Bombay Duck” scene in my forthcoming Perveen Mistry novel, The Mistress of Bhatia House.

Bombay Duck is the Anglo-Indian nickname for a species of lizardfish called Harpoon Nehereus in Latin, and boomla, bummalo, bombil whose habitat is tropical areas of the Indian and Pacific Oceans. They are best know for being fished in Maharashtra, the state that was known in colonial times as Bombay Presidency. Some have suggested that the nickname is related to “Bombay daak,” a famous train of that British ruled era, but that doesn’t seem particularly likely, because people started calling the fish this name before that long distance train existed. It was eaten locally in a number of ways, and it was also canned for export.

So I asked myself, how much of the above information does the reader need to know? And would this fish—which is not as universally enjoyed as say, shrimp or lobster—actually have been served at the Taj Hotel in the early 20th century?

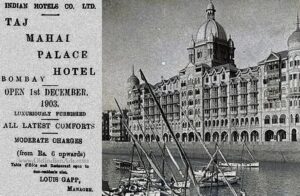

I recalled how two years earlier, I’d walked the halls of the 1903 Taj Mahal Palace hotel with Nisha Dhage, their PR and Marketing director. Nisha had pointed out some of the original dining room menus posted in an archive gallery. I’d snapped a photo of a menu, but it didn’t include Bombay Duck. However, I dug out a history of the Taj Hotel, which did show another menu with Bombay Duck included. That point was sound—but there were other matters to consider.

This is what I originally wrote:

Alice was already studying the menu. “I think I’ll take the Bombay Duck. Will you share? And I’m thinking about Pommes Anna, in case the duck doesn’t come with rice.”

“Yes.” Perveen ran her eyes down the listed dishes. “It depends on whether they are going to make the fish European or Indian.”

The Taj occupied a special place in Bombay. Not only was it the city’s most luxurious hotel, it was built by a Parsi, Jamsetji Tata, who adored The Continent. The menu steered French and Italian.

The waiter arrived late, only after Alice had raised her arm to flag him.

“And how is the Bombay Duck served?” Alice inquired.

“Breadcrumbs fried.”

“That’s it?” Perveen asked. She was accustomed to it prepared many ways, but always with spices and fresh green chili.

“White sauce option.”

“Never mind,” Alice said. “I prefer it cooked in toddy, and with chiles. The Indian way.”

“This is a continental restaurant, madam. My apologies.”

“This is a lovely place,” Alice reassured him. “I’ll take the chilled shrimp cocktail, Chicken Americaine, Potatoes Anna and Salade Lyonnaise. How about you, Perveen?”

Can you guess the rabbit hole I found after reading this? I was compelled to doublecheck the recipe that Alice believes to exist. I went to one of my favorite references, The Essential Parsi Cookbook, written by Bhicoo Manekshaw (1922-2013). I found ten recipes for boomla!

I also wondered: do these fish run during the month of June, prior to rainy season? That’s the time of the novel. Mrs. Manekshaw had no comment on boomla season, so I went to the internet and came away with the impression that they are widely available April to September.

And there was the matter of the waiter, who barely appears at all. The unimportance of people who serve is what I dislike about a lot of British colonial fiction about India. So, I’d have to take care of that. by the same token, I needed to decide Alice’s annoyance about food to remain. An Englishwoman who’s never boiled an egg probably wouldn’t know so much about an Indian dish.

I decided I’d better leave the critical questioning to Perveen.

So here’s the rewrite:

When Perveen reached the Garden Room, she told the maître d’ that Alice would be arriving shortly after her. The maître d’ apologized that lunch orders would be ending in twenty-five minutes and only one table for two was left—close to the hotel wall, not the center of the garden. Did she mind?

“Thank you very much!” Perveen said, glad for the shade and greater privacy this table provided. A young man dressed in white coat with a banded collar and black trousers dashed over from the next table to take her drinks order: a sweet lime for Alice, and salt-lime for herself, both with plenty of club soda and ice. Within ten minutes, the waiter was back with the drinks, and Alice rushed up, face pink from exertion, with wet hair hanging lank to her shoulders.

“You are her guest?” The waiter quickly pulled out the chair for Alice, almost toppling as she moved forward to take her seat.

“Yes. Sorry to look like a drowned rat—I had to race to be first in the showers.”

Perveen laughed. “I rather the think his surprise was because of your missing chapeau.”

She clapped her hand to her crown. “I must have forgotten the damned boater hat in the changing room.”

“Never mind. Just look at the menu—I want to get in the orders before lunch service ends.”

The Taj’s menu steered toward France and sometimes Italy; there were only a handful of Indian dishes on the menu. Given the heat, both women opted for a chilled shrimp cocktail and Salade Lyonnaise. Perveen selected a dish she’d never heard of called Chicken Americaine. Alice inquired about the ingredients contained in the day’s special, a fish called Boomla that bore the Anglo-Indian name “Bombay Duck.”

“Breadcrumbs fried,” the waiter answered, as if he’d said it a thousand times.

“That’s it?” Perveen asked, disappointed. The small, scaleless fish that belonged to the lamprey family was typically cooked with many spices.

“This is a Continental restaurant, madam.” The young man gave her a faintly reproving look.

Alice shrugged. “And a very good restaurant, too. I’ll try it. And did I spy a Black Forest cake on the sweets trolley?” when I came in that you’re now offering Black Forest Torte?”

“Yes, memsahib. I shall set aside a slice of the torte for you. And as for you?” The waiter turned to Perveen.

“No pudding today, thank you.” She had the urge to look at her watch. It felt like the day was being whiled away, when she had so much work trouble to think about.

The waiter recited the order, and when the ladies had nodded their assent, sped off to drop the bill at the next table.

“How interesting that a German cake is appearing on the Taj’s menu so quickly after the war,” Alice said. “In any case, I’m excited to taste chocolate. It’s a rare treat in India.”

I let this last part stand, even though the point about chocolate’s availability is no longer true!