This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

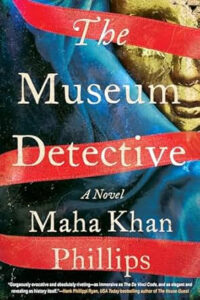

Maha Khan Phillips is a seasoned journalist and novelist based in London. She’s just been published for the first time in the US with her remarkable mystery novel, The Museum Detective. This is a suspenseful story set in Karachi, Pakistan, where Maha was raised, and features a young woman archaeologist, a mysterious female mummy, and a city gone wild with suspense over the find. Karachi comes to pulsating life in this book, which presents a nuanced picture of how women are soldiering forward in the professions and in their own hopes and dreams for good lives. The book’s subplot is an incredible story about a missing teenager, and the power of individual courage, and compassionate friends. Maha answered my questions about her book in front of a rapt audience at The Ivy Bookshop in Baltimore a few weeks ago. Here is how our conversation continued!

When did your interest in archaeology begin—was it with the news story about the mysterious mummy found in Pakistan, or much earlier?

Oh it was much earlier. I can actually pinpoint it exactly to the 5th grade, when we went on a school field trip to the ancient Indus Valley Civilisation site of Mohenjodaro, dating back to approximately 2500BC. I remember the journey to the site vividly – we flew from Karachi in a tiny plane and landed at an airport built especially for the site. We spent the entire day roaming around and exploring. I stood inside the Great Bath, which was probably used for ritualistic bathing, and I closed my eyes and thought of people swimming there thousands of years before. You are not allowed to step in it anymore but back then, it was magical. I often wonder why I didn’t consider archaeology as a career but it took me years to realise how deeply I loved immersing myself in the ancient world. Today I am an enthusiastic amateur who has been lucky enough to visit some really fascinating places.

Where else in the world, besides Egypt, are mummies found?

All over the world, though notably, the Indian sub-continent is one of the few regions where mummies don’t generally tend to exist. As far as I’m aware the Chinchorro mummies of Chile are the oldest known deliberately mummified bodies. Their process involved peeling the skin off a body like a sock, treating the bones, and then reconstructing it with clay, ash and sticks. The skin would then be reattached and painted. Gruesome, but fascinating! In Japan, certain Buddhist monks actually self-mummified through extreme fasting and meditation. The Guanche people of the Canary Islands buried their mummies sitting upright under the ground or in caves. There are mummies in China, in Europe, Siberia, and various parts of Africa.

What is the most interesting mummy fact you found out while researching this novel?

The Victorian obsession with mummies was absolutely bonkers. Despite their horror of cannibalism they were busy grinding up mummy bones into all kinds of potions and lotions and tinctures. From the Middle Ages to the 19th century a substance called ‘mumia’ – derived from mummified bodies – was used across Europe for its healing properties. One detail that really stuck with me was that since the time of the pre-Raphaelites, mummies were used for making pigments. The paint colour ‘mummy brown’ was really popular, particularly during the Victorian era, and it was made from the bones and juices of Egyptian mummies. Amazingly enough it was available for purchase until 1964, when the last manufacturer, C Robertson and Co, announced that it could no longer offer it because it had run out of the body parts.

There’s a true story that inspired The Museum Detective. Can you tell us about it?

In the year 2000 police in Karachi arrested two men attempting to sell a mummified body that they claimed was an ancient Persian princess named Rhodugune, a daughter of King Xerxes, one of Persia’s greatest rulers. They wanted $11 million for her. Police confiscated the body, and it eventually made its way to the National Museum of Karachi. Its discovery caused a sensation. If genuine, it would have re-written history, and the mummy would have been priceless.

A geopolitical tug of war began as a result. Iran demanded her repatriation, and even the Taliban tried to claim that the body was stolen from their land. The international archaeological community got involved as well.

And then Dr Asma Ibrahim, a Karachi-based archaeologist and museologist, proved that the mummy was a fake. She could also have been a murder victim, as evidenced by her broken neck and the blunt force trauma to her body. Once the mummy was exposed as a forgery, global interest vanished. The woman’s body was stripped of its value, and she was eventually buried in an unmarked grave with the help of Asma and the Edhi Foundation. To me that was the most haunting part of the story, how her worth eroded when her body could no longer be commodified. She became yet another unknown victim.

Who is your heroine, Gul Delani?

I loved writing the character of Dr Gul Delani. She’s 36, whip smart and unafraid to speak her mind. She is a museum curator in Karachi with multiple university degrees from around the world, and a background in Egyptology, though she knows many different ancient languages. She has returned to Pakistan for personal reasons and she doesn’t suffer fools gladly – she’s got very little time for showboating or museum politics in particular. Gul is intellectually curious and she believes in justice. She also carries the emotional weight of her niece’s disappearance three years earlier, a mystery that haunts her. Gul is more or less estranged from her family, having rejected the life they expected her to lead. Instead she surrounds herself with a quirky, deeply loyal group of chosen family who support her emotionally and help with her investigative pursuits.

You show us life inside a conservative Islamic nation that shows its citizens enjoying trendy styles, modern music and ostentatious wealth. Is this typical of Karachi? How is Karachi different from Islamabad and Lahore?

Karachi is incredibly complex. It is a sprawling, diverse port city and economic hub with over 20 million people from all walks of life. In the case of The Museum Detective, many of the characters from Gul’s family are from a wealthy elite – modern, flashy and global in outlook. But Karachi also has a rising middle class that engages with both Eastern and Western cultures and values, and communities that are deeply conservative and even extremist. It is a city of contradictions. I haven’t lived in Lahore or Islamabad but from the few times I’ve visited Islamabad, it’s always felt more orderly and bureaucratic – and, personally, a little boring in comparison! Lahore is much more of a cultural heartland and glorious to visit but less of a melting pot. In Gul’s case, her found family – especially her Goan Christian secretary Mrs Fernandes – reflect Karachi’s multi-culturalism.

You name a fundamentalist political party and have its followers threatening action against the heroine, Gul. How do you keep yourself safe when traveling and doing research?

Well, it’s one of those situations where you’re perfectly safe most of the time, but it can never hurt to be careful. There are some things I just wouldn’t do on my own, for example I would never visit some areas that are quite remote in Balochistan or in the interior of Sindh without a convoy of other people, even though that’s where some of the most fascinating archaeological sites are. But I’ve travelled with friends and with family, with and without security, and honestly, I’ve found the bureaucracy to be more frustrating than any actual danger.

There’s a point in the book where scholars of different nations all try to claim a right to the mummy. Is this something that typically happens when there’s an archaeological finding in Asia?

I think it happens any place where there is a cultural, ethnic or historical overlap, or colonial history or looting of stolen heritage. I live in London now, for example, and I often visit The British Museum and stare at the Parthenon Marbles, wondering how their continued possession by the UK can still be justified. In terms of the Indian sub-continent, I think what’s happened to the narrative around the Indus Valley Civilisation is really interesting – who gets to claim ownership of history. There are modern political narratives in both India and Pakistan that try to take a shared multi-ethnic, multi-regional civilisation and fold it into the idea of a single nation state. Clearly, that’s not reality.

Which countries are publishing this book?

To date it’s been published by Soho Crime in the US and is being published this summer by Westland in India and Liberty Books in Pakistan. It will also be published by Shueisha in Japan.

What’s your next book project?

Gul is back! She’s investigating another murder, one that is tied to mythologies around reincarnation, which I’m really excited about. I’m also exploring some elements of faith and superstition, as well as feudalism in Pakistan, and trying to spend some time portraying the younger, edgier side of Karachi as well. I’m not sure how it’s all going to shake out yet but I’m eager to find out!

Sounds like a great book. Thank you.