This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

Can a woman become a successful president?

The mission was attempted just once before in the United States, with Hillary Clinton at the top of the Democratic ticket. Although Hillary won the popular vote, she didn’t win enough electoral college votes and ultimately lost the election to Donald Trump. The question simmers again in this ungodly hot summer, eight years later: could a female politician such as Gretchen Whitmer or Kamala Harris make it to the top?

An estimated 81countries, large and small, have been governed by women leaders. Even places where women’s rights are considered worse than the United States; for example, India, which elected and re-elected one of the world’s most successful and controversial female prime ministers: Indira Gandhi. Indira’s astonishing rise to power in late 1950s India lasted through 1984, and reveals how women can unexpectedly succeed in government.

Indira Priyadarshini Nehru was born in 1917 in Allahabad, the capitol of Uttar Pradesh, an important province in Northern India. She was the only child of Jawaharlal Nehru, a famous leader in the freedom movement, especially in the 1930s and 40s. Indira’s mother, Kamala Kaul Nehru, was chosen as Jawaharlal’s bride by his father, Motilal, a wealthy lawyer who served as president of the Congress Party for several terms. The family was close to Mohandas Gandhi, also called Gandhiji within India and Mahatma Gandhi to his growing international audience.

Both Jawaharlal and Kamala Nehru threw themselves into activism, participating in protests that were violently countered by the police. They were often imprisoned during Indira’s childhood, leaving her to be raised by her grandfather and a large house staff. The grand family home had a revolving door for freedom activists who dined and stayed, inadvertently educating Indira even further. At age 12, Indira started a child activist group called the Army of Monkeys that relayed messages and helped adults involved in political protest. At fifteen, when Gandhi came out of one of his hunger fasts, he requested that Indira serve him a glass of orange juice. But it was still an existence where Indira was educated at schools run by the British, even though she wore the khadi cloth that Gandhiji advocated.

After coming out of prison, Kamala was ill with tuberculosis. Like many wealthy Indians did, the Nehru family went to Europe for the healing air. The Nehrus set up residence in Geneva, Switzerland, where the climate helped Kamala, and they mingled with people of many nationalities and political beliefs. Young Indira traveled by foot and tram by herself to her international day school, another unusual activity for a girl in the 1920s. Shortly after Indira finished high school, Kamala expired from her chronic tuberculosis. Indira grew even closer to her father, who sent her for a broad education that included Shantiniketan in Bengal, and Somerville College in Oxford, England. She was there during the 1930s, when activism for Indian independence was also occurring in England. In these circles, though, Indira was always seen as a small player: when she spoke nervously in front of a group of activists in England, people joked about the squeaky, high pitch of her voice. Other times in India, her quiet nature in group settings led her to be labelled a “dumb doll.”

Yet people took note of her, given her famous parents; especially a handsome young activist from Bombay named Feroze who met her mother in Europe, and following Kamala’s death, became closer to Indira. Born a Parsi with the original surname Ghandy, Feroze changed the spelling in the 1930s, perhaps to align with his mentor, Mahatma Gandhi. In 1942, Indira married Feroze against her father’s wishes, although he and many political power players attended the wedding, which Mahatma Gandhi had warmly endorsed. Because of her new surname, many people mistakenly believed that Indira was connected by marriage or blood to Mahatma Gandhi’s clan.

After marriage, Indira declared a desire to focus on motherhood. She gave birth to two sons, Rajiv and Sanjay, early in her marriage, and in these busy years, turned down opportunities for roles in the party. Yet in 1947, when her father was elected as the first prime minister in independent India, she faced an offer that was hard to refuse.

Jawaharlal requested her support as a political mate, asking her to leave Feroze to come to live with him in New Delhi and serve as his official hostess. By this time, Feroze was busy in Lahore running the National Herald, a newspaper founded by his father-in-law. There were also strains in the marriage caused by Feroze’s extramarital relationships.

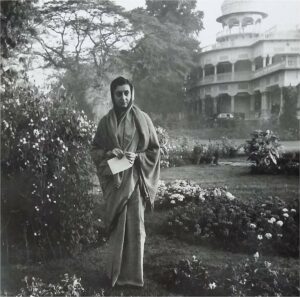

Indira took her sons with her to her father’s place: Teen Murti Bhavan, the “three statues home,” resting on 30 acres in Delhi. She hosted visitors and accompanied her father on political missions. Within a few years’ time, Feroze became largely absent from her life. He died of a heart attack in 1960 at the age of 47, an event that Indira spoke sadly about, despite the long separation between then. She never married again.

Indira had gradually increased her political activities began in the 1950s, and was elected as President of the Congress Party in 1955. In this role, she assisted her prime minister father with challenges that arose nationally, including her infamous decision to disband the state of Kerala’s elected Communist government in 1959.

Jawaharlal Nehru died as prime minister in 1964 from a heart attack. The next elected prime minister was a Congress Party politician Lal Bahadur Shastri, who offered Indira a choice of appointments. She chose Minister of Information and Broadcasting, a job that wasn’t especially prominent. In January 1966, Shastri visited Tashkent and had a sudden violent heart attack, turning blue from a cause that was never discovered. The Congress Party elected Indira as the next prime minister. Yet shortly after stepping into the role, the right wing of the Congress Party challenged her. She won a narrow victory in the 1967 election and had to serve with a deputy prime minister, Moraji Desai, a politician whom she didn’t trust.

In 1971, she had a strong reelection victory, but there was no time to relax. Trouble was brewing in Eastern Pakistan, where the Bengali-Urdu speaking population wanted to become its own country. These guerrilla fighters were aided by Indian troops, at Indira’s direction. India’s invasion of Pakistan resulted in the war finishing quickly and the creation of Bangladesh. This triumph enhanced Gandhi’s image and led her New Congress Party to a landslide victory in national elections in 1972. However, India’s food shortages, price inflation and regional disputes made the next few years challenging. A rival politician with his own party argued that she’d been fraudulently elected in the 1975 election.

Indira declared a state of emergency, giving herself great powers to arrest political opponents and suspend a free press. During this time, her younger son Sanjay assumed a large role in her government and directed a mass sterilization of India’s rural poor. When Indira finally ended the emergency and agreed to hold a new election, she lost to the rival Janata Party. A trial followed in which she was convicted of corruption and briefly imprisoned. But soon thereafter, the rival party fell apart, and she ran for prime minister on the Congress party ticket in 1980, winning again. Nobody had called her a dumb doll for years. Her nickname had become Iron Lady.

Indira Gandhi seemed blessed with election magic. Yet her very difficult challenge in the 1980s was the rise of Sikh separatists in the state of Punjab. India She ordered the army to storm a holy site, the Golden Temple in Amritsar, where Sikh militants were believed to be staying. The resulting carnage was not forgiven, and in 1984, one of her personal bodyguards, a Sikh who was sympathetic to the militants, shot her to death while she was taking a morning stroll through her beautiful garden.

As things stand, the incumbent president, Joe Biden, will run again on the top of the Democratic ticket. And I don’t expect any of the possible women candidates for president this year will have such a wild, and ultimately tragic, political story.

But still . . .

Note the ways that Indira Gandhi and Kamala Harris are similar. Both grew up with significant childhood independence, and they became fluent in multiple cultures, given their connections to different countries and religions. They became activists in young adulthood, and they selected husbands with different religions. And these husbands weren’t the ones who gave them assistance in their careers; father-figure politicians played a role.

Sometimes a preponderance of small advantages can add up to possibility. But in 2024, will the chance be there?

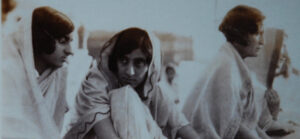

Thanks to the Indira Gandhi Memorial Trust for all photos used in this essay