This post originally appeared on Murder Is Everywhere.

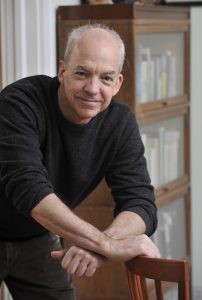

In my youth at the long-gone Baltimore Evening Sun newspaper, Dan Fesperman was a successful hard news reporter who was also extremely kind to the new kids: i.e., the interns and new hires straight out of college like myself who needed tips about where to go to actually get the facts for an article due in three hours’ time. Dan rose in stature to become a foreign correspondent for the company’s morning paper, the larger-circulation Baltimore Sun. Dan covered three wars and spent many years in Eastern Europe, the Middle East and South Asia. Incredibly, his first three thrillers were written while he was still reporting for the paper. Luckily for us, he retired and has sent eleven more books into the world. Dan’s fiction has won two Dagger Awards from the UK Crime Writers Association, the Barry Award for Best Thriller, and the Dashiell Hammett Prize from the International Association of Crime Writers. PARIAH, his latest effort, is set in a fictional Eastern European country called Bolrovia and stars a disgraced comedian (the pariah) turned bumbling (and also brilliant) spy. I asked Dan a few questions about his career and this hilarious and exciting novel. It’s also notable that Dan narrates the audiobook version of PARIAH, and it’s a tour de force with many different accents—as good as listening to the late John Le Carré read his own work. Thank you, Dan, for being a guest author at Murder is Everywhere! —Sujata Massey

Tell us about the spark that became the plot of your newest book, Pariah.

Pariah came to life partly out of my fascination with the strange love affair that developed a while back between American conservatives and Viktor Orban, the strongman president of Hungary, whose power grab over the past few decades presaged a lot of what is happening now in Washington. And, by that, I mean not only Orban’s ultra-nationalism, but also his ability to clear away most of Hungary’s checks and balances on presidential power. He clamped down on the news media, universities, immigrants, dissenters, and so on. American conservatives saw that, loved it, and have set out with some success to replicate it, which is why we’re now seeing similar tactics from Trump and Stephen Miller. And when you start to contemplate how tricky things might be for the CIA to build a network of spies in a place with those kinds of connections, and that kind of affinity to certain elements here, well, a lot of interesting scenarios quickly come to mind. So I was off and running.

You covered the war in Bosnia in 1992-95. You wrote about the time during and right after the wars in Sarajevo and Croatia in the beginning of your career as a novelist—the two Vlado Petric books. Yet, this novel is set in 2023, and the country, Bolrovia, feels like it could be one of several Eastern European countries that are very popular to visit now.

I decided pretty early that I wanted to set the book in a fictional country instead of Hungary, partly for legal reasons, but more so because it freed me up to make the place a better fit for my characters and the plot. At first, I thought that would difficult, even a slog, but I quickly began to enjoy building my own world on the rough template of many of the places I’d visited and worked in. My hope was that Bolrovia, and particularly its capital city, Blatsk, would feel instantly familiar to anyone who has been to Prague, Budapest, Zagreb or Krakow. The city’s more compact scale probably most closely evokes Krakow, while its drearier outlying areas bring to mind Zagreb, Budapest and even East Berlin. The Bolrovian countryside feels to me like some hybrid of Poland, Hungary and East Germany. And, as with most of those locations, Bolrovia’s 20th Century history casts a long and deep shadow—a brutal era of Nazi occupation followed in close order by four decades of Soviet domination, which ended abruptly and peacefully in 1989. This is a place in which both the leaders and their subjects know what a crackdown looks and feels like, and the many forms that can take. But I think the most pleasant byproduct of using a fictional setting was that I instantly felt more open to the idea of satire, and that mood soon began to infiltrate my prose. When you then choose a washed-up comedian as your main point-of-view character, the effect is accentuated, because this is someone who will see the inherent absurdity of almost any situation, no matter how dire.

Talk to us about Hal and whether there are real-life influences of his character.

Anytime your main character is a comedian-turned-Congressman brought down by a Me-Too moment, Al Franken, the SNL writer-comedian who became a Senator, immediately comes to mind. But I definitely wouldn’t say he was a model for Hal. Hal is quite different, both comedically and in terms of his more disgraceful moment of infamy. He is a bright fellow who knows he has succeeded partly by cheapening his humor with more lowbrow material, nor did he ever take himself seriously as a politician, and in some ways he believes he has gotten what he deserves. As the book opens, he’s laying low on a Caribbean island, aimlessly in search of anything that might offer a new sense of purpose. So, when three CIA operatives approach him to say, “Hey, there’s this quasi-dictator in Bolrovia who loves your stuff and has invited you for a visit, and we’d like you to accept the invitation in order to spy for us,” well, he just might be desperate enough to take them up on it.

The leader of this CIA contingent, and Hal’s handler in Bolrovia, is Lauren Witt, someone with her own reservations about this op. Is she like any CIA agent you’ve met?

That’s impossible to know, because CIA officers out in the field can be operating under cover as aid workers, business people, or, if they have diplomatic cover, they might have some sort of title at the U.S. embassy like “political attache,” or whatever. As a foreign correspondent I sometimes had off-the-record briefings with people who I suspected were working for the Agency, especially when they had more questions about what I’d seen out in the field than I had for them. As for women working in those jobs, I’ve obtained most of that kind of information either from ex-employees who’ve been kind enough to speak to me, or by culling insights from declassified archival material.

How do you manage to research details of CIA work? Tom Clancy got entree to look at warships. Do you have fans in the organization who have helped?

You might be surprised by how helpful ex-CIA people can be once they know you’re writing fiction, and that you won’t be quoting them by name. About fifteen years ago, while doing research for a TV project that was never produced, I interviewed at length around two dozen people whose CIA careers dated back to the late 1940s. Some had even worked with the CIA’s predecessor organization, the OSS. I learned a ton, not only about tradecraft abroad but also about interoffice tensions and rivalries, their social lives in Europe and in Georgetown, and the whole ethos of a life in which you can almost never reveal what you’re really doing, not even to the people closest to you. That material helped shape not just this book but several others, and I continue to seek out those kinds of interviews to inform my work. There is also a load of interesting archival material that the CIA has declassified. Additionally, once you begin writing about this stuff, former employees will get in touch with you, unsolicited, to offer their own tales and insights, either by email or by approaching me after book signings. Plenty of this material creeps into my books. The more you learn, the more you keep learning.

Were you inspired by any Graham Greene novels when writing this book? Our Man in Havana comes to mind. Who are some of your other admired writers in the genre?

Yes, I suppose that influence is pretty obvious. In fact one of my early prospective titles was Our Man in Bolrovia. Another was The Comedian, a nod to Greene’s The Comedians, although that was a far darker novel of his. I read most of his fiction back in my mid-to-late 20s, so I’m sure those influences are still at play somewhere deep in my head. As for others? Well, John Le Carré always comes to mind, mostly for the way that he always put character ahead of action. Among my contemporaries, there are so many to choose from, so I’ll mention a handful even as I cringe because I’ll wish later I’d named more: Charlie Cumming, David McCloskey, Ilana (I.S.) Berry, Paul Vidich, Mick Herron, and… okay, I’d better stop before I run on for another paragraph.

I really think there should be more comic novels in general, and I absolutely love your comic spy novel. Do you think you would do this again (and forgive me if you wrote an earlier funny one that I don’t know about)?

With regard to doing something like this again, my rule is always “Never say never.” As for earlier novels, I didn’t think I had written a humorous one, but in the quite generous and perceptive review of Pariah that ran in the Sunday New York Times Book Review, writer Christopher Bollen mentioned in passing the humor of a previous book of mine, Layover in Dubai, so I went back and read the opening chapter and, yes, it did have a similar tone, at least in those opening pages. It also featured a character who, like Hal, was quickly in over his head, although in this case it was a hapless and naive businessman who got caught up in the darker doings of a colleague. Having said that, the book I’m working on now is in a more serious vein. It’s an update of my main character from Winter Work, an East German spymaster named Emil Grimm, who we’ll rejoin about five years after the events of that book.

Your settings in past have included Sarajevo, New York City, Afghanistan, Germany, Dubai. What does your passport look like? Are you often traveling to fact check this material, or are some places better written about from memory?

My expired passports are probably the most interesting ones, since they include all those visa stamps from wartime travels, or from my first visits to the Middle East. But I have continued to travel on my own dime to many of these places because, even if I’ve already been somewhere, I always feel as if a refresher course is necessary if I’m going to set my next novel there. I returned to Berlin in April 2024 for the book I’m working on now, and I’m sure I’ll continue to do this going forward. As you know yourself, from your own writing and travels, it’s one of the best fringe benefits of being an author.